|

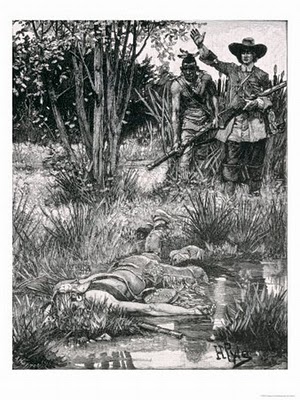

By early July, over 400 of Metacomet's (aka King Philip to the English) warriors had surrendered to the colonists. Metacomet took refuge in the Assowamset Swamp, below Providence, close to where the war had started. Metacomet was tracked down by colony-allied Native Americans led by Captain Benjamin Church and Captain Josiah Standish of the Plymouth Colony. Metacomet was shot and killed by a native named John Alderman on August 12, 1676. His corpse was beheaded,before he was drawn and quarter a traditional treatment of criminals in this era. His head was displayed in Plymouth for twenty years.

With King Philip's death, the most horrific war on the North American continent in terms of percentage of the population who died came to an end. In "The Immigrant". Lydia Law learned of King Philip's death, some 5 days later while attending the meetinghouse on the Sabbath, which she retold John upon her return. |

Chapter Forty-six

On August 17, 1676, Lydia and the boys were dressing for the Sabbath. “John, will thou be attending with us?” asked Lydia.

John didn’t respond, so Lydia glared to force an answer.

“Got me corn to pick,” he said.

“Thou hast tomorrow for ye corn harvest.”

“Must be done today. Tomorrow me harvests me hay.” Lydia’s stare persisted, and John said, “King Philip has all but vanished. John Junior will protect you.” John turned to his fifteen year old son, “Aye laddie, when me be your age, me be a pikeman fighting for King Charles.”

“It’s not protection my heart doth desire, but our family as one on the Sabbath,” said Lydia.

John frowned and headed to his fields.

Lydia had grown accustomed to her family attending the meetinghouse each Sabbath, an odd benefit of the war. But she had heard the gossip too. John had endured much, and she was sympathetic to why the corn absolutely had to be picked this day. Most likely, future Sabbaths would bring other chores John absolutely had to do. Though disappointed, she understood and left, comforted by the thought she had married a really good man.

John Junior shouldered his father’s musket, just as he imagined his father had shouldered his pike years ago. He stepped with pride as he led his mother and brother on the path toward the Shepherds. John stopped picking his corn to watch his family depart. As he watched his eldest son leading the family, he scrunched his shoulders as shivers shot up his spine. Aye, me lad be a man this day.

Throughout the day, the sky remained cloudless, and John paused often to wipe his brow. By mid-afternoon, he was finished. He slung the sack of corn over his shoulder and headed down the rise. After storing it in the shed, he stripped and, with energetic anticipation of what he desperately needed, bounded into the river. He splashed around until the shock of the cold water wore off. He dunked, ran his fingers through his gnarled hair, and treaded water to remain in the cool current. But eventually his arms tired, and he floated into the reeds. His fatigued muscles were now soothed, and the sun warmed his face, providing a welcome contrast to his submerged body. Aye, what a glorious Sabbath it be. He thought about crossing back to the riverbank closer to his home, but he was too comfortable and stayed put.

“John, what a glorious Sabbath it is,” said an excited Lydia as she and her two sons suddenly appeared on the bridge.

Startled, John inched further into reeds and submerged to his chin

“Thou will not believe the good news.” Lydia ran across the bridge to the riverbank across from John. “King Philip is dead. Shot down in Miery Swamp near Mount Hope[1] on Wednesday last. Praise the Lord.”

“Aye, praise the Lord,” said a still crouched and self-conscious John.

“Our burden hath ended. Praise the Lord indeed.” Lydia now wondered why John’s response had been halfhearted and why he was still crouched in water. Her eyes widened, and she moved her fingertips to her mouth. “Mercy John, thou art like the baby Moses in ye reeds. I will tarry no longer, so thou can come hither.” Lydia ushered her sons up the rise.

John inched out of the reeds and called out. “Lydia, can you fetch me breeches?”

[1] Miery Swamp is in present day Bristol, Rhode Island, 50 miles southwest from Plymouth, Massachusetts. At the intersection of Tower Street (at milepost 0.7) and Metacom Avenue (Rhode Island Route 136) in Bristol is a marker to commemorate where King Philip fell on 12 August 1676, which was place by the Rhode Island Historical Society in 1877 as shown above.

On August 17, 1676, Lydia and the boys were dressing for the Sabbath. “John, will thou be attending with us?” asked Lydia.

John didn’t respond, so Lydia glared to force an answer.

“Got me corn to pick,” he said.

“Thou hast tomorrow for ye corn harvest.”

“Must be done today. Tomorrow me harvests me hay.” Lydia’s stare persisted, and John said, “King Philip has all but vanished. John Junior will protect you.” John turned to his fifteen year old son, “Aye laddie, when me be your age, me be a pikeman fighting for King Charles.”

“It’s not protection my heart doth desire, but our family as one on the Sabbath,” said Lydia.

John frowned and headed to his fields.

Lydia had grown accustomed to her family attending the meetinghouse each Sabbath, an odd benefit of the war. But she had heard the gossip too. John had endured much, and she was sympathetic to why the corn absolutely had to be picked this day. Most likely, future Sabbaths would bring other chores John absolutely had to do. Though disappointed, she understood and left, comforted by the thought she had married a really good man.

John Junior shouldered his father’s musket, just as he imagined his father had shouldered his pike years ago. He stepped with pride as he led his mother and brother on the path toward the Shepherds. John stopped picking his corn to watch his family depart. As he watched his eldest son leading the family, he scrunched his shoulders as shivers shot up his spine. Aye, me lad be a man this day.

Throughout the day, the sky remained cloudless, and John paused often to wipe his brow. By mid-afternoon, he was finished. He slung the sack of corn over his shoulder and headed down the rise. After storing it in the shed, he stripped and, with energetic anticipation of what he desperately needed, bounded into the river. He splashed around until the shock of the cold water wore off. He dunked, ran his fingers through his gnarled hair, and treaded water to remain in the cool current. But eventually his arms tired, and he floated into the reeds. His fatigued muscles were now soothed, and the sun warmed his face, providing a welcome contrast to his submerged body. Aye, what a glorious Sabbath it be. He thought about crossing back to the riverbank closer to his home, but he was too comfortable and stayed put.

“John, what a glorious Sabbath it is,” said an excited Lydia as she and her two sons suddenly appeared on the bridge.

Startled, John inched further into reeds and submerged to his chin

“Thou will not believe the good news.” Lydia ran across the bridge to the riverbank across from John. “King Philip is dead. Shot down in Miery Swamp near Mount Hope[1] on Wednesday last. Praise the Lord.”

“Aye, praise the Lord,” said a still crouched and self-conscious John.

“Our burden hath ended. Praise the Lord indeed.” Lydia now wondered why John’s response had been halfhearted and why he was still crouched in water. Her eyes widened, and she moved her fingertips to her mouth. “Mercy John, thou art like the baby Moses in ye reeds. I will tarry no longer, so thou can come hither.” Lydia ushered her sons up the rise.

John inched out of the reeds and called out. “Lydia, can you fetch me breeches?”

[1] Miery Swamp is in present day Bristol, Rhode Island, 50 miles southwest from Plymouth, Massachusetts. At the intersection of Tower Street (at milepost 0.7) and Metacom Avenue (Rhode Island Route 136) in Bristol is a marker to commemorate where King Philip fell on 12 August 1676, which was place by the Rhode Island Historical Society in 1877 as shown above.