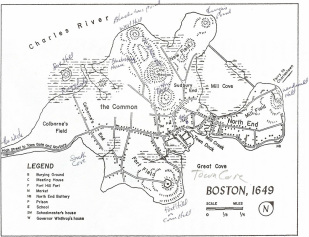

In the winter of 1650 - 1651 the Unity arrived at Charlestown. Below were Scottish prisoners captured by Lord Cromwell on 3 September 1650 at Doon Hill, Dunbar, Scotland. The dead on that day were the fortunate ones, their ordeal was over. But for the prisoners, theirs had just begun. As the Unity bumped against the pier and dock workers yelled, tossed lines and secured the ship for unloading, the prisoners would soon be indentured servants. Would this new status finally end their ordeal or would life in this distant land bring further suffering?

Chapter Nine

Charlestown, Massachusetts Bay Colony

Winter 1650 – 1651

“What cheer,” said John Gifford to an approaching William Awbrey, his business associate.

Standing on the pier Awbrey gestured to the sea, and his cloak draped off his extended arm. Its graceful folds hung, offering an accentuating backdrop for his knee-high leather boots. “Storm clouds loom on ye horizon.” He scrunched his shoulders and said, “And there is bite in the air.”

“Ye storm clouds are too distant,” said Gifford. “But thither is The Unity, a godsend for our problems.”

“Some, but not all. I have seen thy account books.”

“Ah William, always so skeptical.”

“We need craftsmen, skilled ironworkers and…”

“Exactly what Becx promised, and exactly what will be arriving.”

“Dost thou believe Scotland has any skilled men in their land?”

Gifford turned away from the open sea and stood with arms akimbo. “We will train them. May cost a farthing or two, but worth the outlay.”

“First thou must feed them and …”

“Cease William, thou hast soured this beautiful day enough.”

Gifford left Awbrey and hurried along the dock as workers scurried to their posts. Awbrey followed, clicking his walking cane as he ambled. Securing lines were tossed to the ship to ready it for unloading. Gifford remained buoyant. His problems would be solved. When Awbrey sidled close, Gifford stepped away.

Below the top deck of the Unity, the docking had stirred the prisoners from their despair. John crouched and stepped around men toward a light coming through a slit. His eyeball swept across the harbor to land, a welcoming sight he hadn’t seen since leaving London several weeks earlier. On one of those days while on the Atlantic, John thought he had turned fifteen years old. He continued perusing the shoreline until the prisoners were ordered to move topside.

John braced against the ship’s side and stepped cautiously until his legs found strength. The sun beamed down the ladder, and invigorating salt air refreshed his lungs. As he moved further up the ladder, the sun blinded him. Disoriented, he crawled out and scurried, like a ship’s rat, away from the hole. He rose on his tiptoes, enjoying his freedom from the restrictive, ever-present, low-hanging ceiling. He inhaled and strained his face toward the sun while surveying the harbor’s surroundings. Unlike London, only a few buildings dotted the landscape, a new world with boundless land and endless opportunities.

A boarding plank rumbled into position, and the prisoners neared it. John was among frail, half-clothed, odorous, hollow-eyed Scots, who were struggling to remain erect. Yet, as he looked out from this despair, below were wide-eyed, rosy-cheeked, properly clothed men, his future. A man wrapped in a finely woven wool cloak stood straddling an ornately carved cane. As the two groups, prisoners and business men, assessed their stark differences, John wondered if someday he might be among the fortunate.

Gifford moved to Awbrey and said, “Becx promised only the hearty.”

“Probably were hearty when they left England.”

“Well, clothe and fatten them. They are of no use now.” The air wafted from the top deck, and Gifford’s nose twitched. “But wash them first.”

As the Scots staggered down the ramp, one slipped, and his flailing arm hooked a guide line that saved him from tumbling into the harbor. The dock workers gasped, but those disembarking were too weak to respond and too inured to empathize. Once offloaded, the captives milled and occasionally flexed their legs. John turned east. Scotland was far beyond the divide, and he knew he would never see it again. Yet he wasn’t depressed and didn’t know why. When Gifford and Awbrey neared, he congregated with his countrymen.

Gifford said, “Welcome to ye new home. Thou art indentured for seven years, and then ye will be free.” Gifford’s optimism was waning, and his distrust of Becx was growing. “Have any of ye worked at an ironworks?”

The disheveled Scots muttered and looked at one another. Awbrey grew smug, irritating Gifford further. “Can ye fell trees?” asked Gifford.

Several hands arose, and one said, “Me can use me pike, real goot.” The Scots laughed, and a few nodded their heads. They were becoming comfortable with their surroundings.

But the Scottish brogue baffled Gifford. “Scottish man, I did not understand thee.”

Another bellowed, “He be a pikeman and has done his share of felling English bastards.” The Scots roared, and their confidence continued to increase.

“Pikeman, dost thou know Goodman Awbrey and I are English?”

Quiet ensued; of course the Scots knew Awbrey and Gifford were English, they had forgotten that fact for only a moment. Yet Gifford seized it to laud his birthright, not as menacingly as his countrymen had done at Doon Hill, but, nonetheless, to stress English superiority. The Scots’ fragile confidence was devastated. They shrunk together, except for John who was focused on Awbrey again. His cloak had opened to reveal an embroidered jerkin, flared at the waist, with shiny buttons that tailored it perfectly from his torso to his shoulders.

“Who’s a farmer?” asked Gifford. Several muttered, and a few raised their hands. “Or a shepherd?”

John’s hand shot up as he looked at Awbrey. “Me be a good shepherd,” said John. Awbrey tilted his head, and John appreciated the acknowledgement, oblivious to the disapproving head shakes from his countrymen.

Gifford turned to Awbrey and smiled. “Woodsmen, shepherds, these thieving Colonists shant get a farthing from us anymore for their timber and scrawny livestock. There is thy precious ledger books’ savings. Now dost thou see?”

Awbrey didn’t answer the question, and Gifford turned back to the Scots. “Dost ye have questions?”

A hunched over Scot gripped his stomach and said, “Aye, gae me food for me belly.”

Perplexed by the Scottish dialect, Gifford turned to Awbrey who said, “He wants to eat. Hard to believe it’s the same language.”

“William, it isn’t,” said Gifford.

Awbrey roared, and by wont, the Scots drew close, unsure what Awbrey’s laughter meant. But John remained aloof, focused on Awbrey’s attire and fueled with the hope of someday being a prosperous shepherd.

*****

The Scots bunked at the warehouse while waiting to be dispersed. Many were in poor health and unable to work immediately. Over time, John and many others went to the Ironworks on the Saugus River, others boarded the Unity and sailed north to the Piscataqua River and a few were indentured to locals. Most were unskilled in ironwork operations, just as Awbrey had foretold. The unskilled grew crops, cut hay, felled timber and mined bog ore. The few with initiative and intelligence were trained as colliers and furnace men, but educating them was slow and expensive. Gifford’s problems persisted. Becx’s cheap labor was exactly the opposite, an expensive burden on a struggling operation.

Charlestown, Massachusetts Bay Colony

Winter 1650 – 1651

“What cheer,” said John Gifford to an approaching William Awbrey, his business associate.

Standing on the pier Awbrey gestured to the sea, and his cloak draped off his extended arm. Its graceful folds hung, offering an accentuating backdrop for his knee-high leather boots. “Storm clouds loom on ye horizon.” He scrunched his shoulders and said, “And there is bite in the air.”

“Ye storm clouds are too distant,” said Gifford. “But thither is The Unity, a godsend for our problems.”

“Some, but not all. I have seen thy account books.”

“Ah William, always so skeptical.”

“We need craftsmen, skilled ironworkers and…”

“Exactly what Becx promised, and exactly what will be arriving.”

“Dost thou believe Scotland has any skilled men in their land?”

Gifford turned away from the open sea and stood with arms akimbo. “We will train them. May cost a farthing or two, but worth the outlay.”

“First thou must feed them and …”

“Cease William, thou hast soured this beautiful day enough.”

Gifford left Awbrey and hurried along the dock as workers scurried to their posts. Awbrey followed, clicking his walking cane as he ambled. Securing lines were tossed to the ship to ready it for unloading. Gifford remained buoyant. His problems would be solved. When Awbrey sidled close, Gifford stepped away.

Below the top deck of the Unity, the docking had stirred the prisoners from their despair. John crouched and stepped around men toward a light coming through a slit. His eyeball swept across the harbor to land, a welcoming sight he hadn’t seen since leaving London several weeks earlier. On one of those days while on the Atlantic, John thought he had turned fifteen years old. He continued perusing the shoreline until the prisoners were ordered to move topside.

John braced against the ship’s side and stepped cautiously until his legs found strength. The sun beamed down the ladder, and invigorating salt air refreshed his lungs. As he moved further up the ladder, the sun blinded him. Disoriented, he crawled out and scurried, like a ship’s rat, away from the hole. He rose on his tiptoes, enjoying his freedom from the restrictive, ever-present, low-hanging ceiling. He inhaled and strained his face toward the sun while surveying the harbor’s surroundings. Unlike London, only a few buildings dotted the landscape, a new world with boundless land and endless opportunities.

A boarding plank rumbled into position, and the prisoners neared it. John was among frail, half-clothed, odorous, hollow-eyed Scots, who were struggling to remain erect. Yet, as he looked out from this despair, below were wide-eyed, rosy-cheeked, properly clothed men, his future. A man wrapped in a finely woven wool cloak stood straddling an ornately carved cane. As the two groups, prisoners and business men, assessed their stark differences, John wondered if someday he might be among the fortunate.

Gifford moved to Awbrey and said, “Becx promised only the hearty.”

“Probably were hearty when they left England.”

“Well, clothe and fatten them. They are of no use now.” The air wafted from the top deck, and Gifford’s nose twitched. “But wash them first.”

As the Scots staggered down the ramp, one slipped, and his flailing arm hooked a guide line that saved him from tumbling into the harbor. The dock workers gasped, but those disembarking were too weak to respond and too inured to empathize. Once offloaded, the captives milled and occasionally flexed their legs. John turned east. Scotland was far beyond the divide, and he knew he would never see it again. Yet he wasn’t depressed and didn’t know why. When Gifford and Awbrey neared, he congregated with his countrymen.

Gifford said, “Welcome to ye new home. Thou art indentured for seven years, and then ye will be free.” Gifford’s optimism was waning, and his distrust of Becx was growing. “Have any of ye worked at an ironworks?”

The disheveled Scots muttered and looked at one another. Awbrey grew smug, irritating Gifford further. “Can ye fell trees?” asked Gifford.

Several hands arose, and one said, “Me can use me pike, real goot.” The Scots laughed, and a few nodded their heads. They were becoming comfortable with their surroundings.

But the Scottish brogue baffled Gifford. “Scottish man, I did not understand thee.”

Another bellowed, “He be a pikeman and has done his share of felling English bastards.” The Scots roared, and their confidence continued to increase.

“Pikeman, dost thou know Goodman Awbrey and I are English?”

Quiet ensued; of course the Scots knew Awbrey and Gifford were English, they had forgotten that fact for only a moment. Yet Gifford seized it to laud his birthright, not as menacingly as his countrymen had done at Doon Hill, but, nonetheless, to stress English superiority. The Scots’ fragile confidence was devastated. They shrunk together, except for John who was focused on Awbrey again. His cloak had opened to reveal an embroidered jerkin, flared at the waist, with shiny buttons that tailored it perfectly from his torso to his shoulders.

“Who’s a farmer?” asked Gifford. Several muttered, and a few raised their hands. “Or a shepherd?”

John’s hand shot up as he looked at Awbrey. “Me be a good shepherd,” said John. Awbrey tilted his head, and John appreciated the acknowledgement, oblivious to the disapproving head shakes from his countrymen.

Gifford turned to Awbrey and smiled. “Woodsmen, shepherds, these thieving Colonists shant get a farthing from us anymore for their timber and scrawny livestock. There is thy precious ledger books’ savings. Now dost thou see?”

Awbrey didn’t answer the question, and Gifford turned back to the Scots. “Dost ye have questions?”

A hunched over Scot gripped his stomach and said, “Aye, gae me food for me belly.”

Perplexed by the Scottish dialect, Gifford turned to Awbrey who said, “He wants to eat. Hard to believe it’s the same language.”

“William, it isn’t,” said Gifford.

Awbrey roared, and by wont, the Scots drew close, unsure what Awbrey’s laughter meant. But John remained aloof, focused on Awbrey’s attire and fueled with the hope of someday being a prosperous shepherd.

*****

The Scots bunked at the warehouse while waiting to be dispersed. Many were in poor health and unable to work immediately. Over time, John and many others went to the Ironworks on the Saugus River, others boarded the Unity and sailed north to the Piscataqua River and a few were indentured to locals. Most were unskilled in ironwork operations, just as Awbrey had foretold. The unskilled grew crops, cut hay, felled timber and mined bog ore. The few with initiative and intelligence were trained as colliers and furnace men, but educating them was slow and expensive. Gifford’s problems persisted. Becx’s cheap labor was exactly the opposite, an expensive burden on a struggling operation.