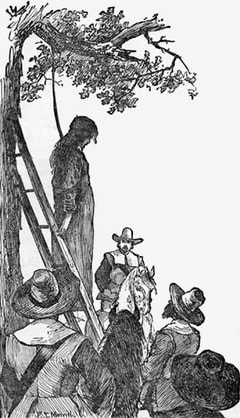

The 1630 - 1640 great migration was fueled in large part by those seeking religious freedom. These emigres, unified in faith and settled far from home, over time created a Puritan Theocracy. Ironically, the emigrants had fled religious persecution only to become oppressors; they were most spiteful toward the Quakers. On 27 October 1659, Quakers William Robinson, Marmaduke Stephenson, and Mary Dyer were scheduled to be hanged in Boston. Each climbed the ladder, and a noose hanging from an elm tree was tightened around each’s neck. William went first, followed by Marmaduke, and each died once the ladder was removed. Mary, with hands and legs bound and a handkerchief covering her face waited on the ladder. However, her life was spared by a last minute reprieve.  Some twenty years earlier, Mary gave birth to a deformed stillborn. Realizing the theological implications, she concealed the circumstances of her birth and buried the child secretly. Once Governor Winthrop learned of the situation, he investigated further and unearthed Mary’s secret. The Governor believed Mary’s monstrous birth was further proof of God’s disapproval of her antinomian heretics. She fled Massachusetts for Rhode Island to join Anne Hutchinson, Roger Williams, and other persecuted exiles. Later, Mary returned to England and became inspired by George Fox and his Society of Friends. She returned to Boston in 1657. The day after her reprieve, Mary wrote to the General Court refusing to accept her pardon's terms. While the General Court attempted to soften the terms, Mary left for Rhode Island again, only to return in the spring of 1660. She was resolute; either the authorities would change their laws or they would need to hang a woman. On 1 June 1660, she was led to the gallows and given the opportunity to recant her beliefs. "Nay, I cannot;” said Mary, “for in obedience to the will of the Lord God I came, and in his will I abide faithful to the death." The ladder was removed, and she died soon thereafter.  William Leddra, the fourth of the Boston Martyrs, like the others was pure of character. Even so, he endured beatings and banishment for preaching in Massachusetts. When he defied his banishment and returned in 1660, he was arrested, charged with sympathizing with the Quakers who were executed before him, refusing to remove his hat, and using "thee" and "thou" to imply equality of all people. Imprisoned, he lay chained to a log throughout the winter without heat. In a dark cell before being led to his gallows on 24 March 1661, he wrote to his wife. Standing beneath the elm with arms tied while a noose swayed in the breeze, he said, "For bearing my testimony for the Lord against deceivers and the deceived, I am brought here to suffer." His last words were, "Lord Jesus, receive my spirit." The martyrdom created an outrage throughout the colony, which eventually reached England. In September 1661, the king directed that all legal actions against the Quaker cease. Did the king's order suppress the theocratic zeal? Perhaps. Here is a relevant scene from “The Immigrant” November 1661 Governor’s Chambers, Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony “I fear ye hangings of Mary Dyer and William Leddra have returned to haunt us,” said the Governor’s aide. “Those Quakers were hung in Boston Common by order of ye Great Court of ye Commonwealth,” said Governor Endicott. “Why dost thee have dread-filled thoughts now?” “Samuel Shattuck hath returned with a message,” said the aide. “A message from that banished Quaker hath no meaning in ye Commonwealth.” “Governor, the message hath been scribed on parchment and hath a seal.” The Governor moved to the window and looked out at the graying skies. He grimaced and turned back. “Allow ye Quaker into my chamber.” The door opened, and a plainly dressed man with a wide brim hat entered, holding a sealed parchment. He lowered his head to the Governor. “How dare thee show disrespect for thy Governor?” said the aide. Shattuck cowered as the aide grabbed the crown of his hat and yanked it off of his head. The aide placed the crumbled hat on the desk, took the parchment, and handed it to the Governor. The Governor broke the seal, and his eyes shifted to the signature and seal at the bottom. He dropped his hand that held the parchment to his side and removed his hat with his other hand. “It’s from His Royal Majesty, Charles II,” said the Governor as he bowed his head. He held the parchment up, squinted, and moved to the window for more light. An anxious aide and a now less concerned Shattuck watched the straight-faced Governor. “We shall obey as thy Majesty commands,” said the Governor. “Thou may take leave, Samuel Shattuck.” Once the door shut, the Governor tightened his grip on the parchment and turned to his aide. “Summon the magistrates and ministers forthwith.” “And what shall I say to them?” “Tell them His Majesty commands jailed Quakers, from this day forth, will be tried on English soil.” The aide bowed his head. “Very well, as thou command.” “To the contrary, it is quite unwell. Once in England, ye Quakers will bear nothing but false witness against our Commonwealth justice, prevaricating dogs to amuse our Sovereign.” “Then let ye dogs roam and howl in the Commonwealth and not whimper at the foot of our Sovereign,” said the aide. “Shall I fetch William Sutton, ye Boston jailer?” “Pray tell, why?” “If ye jail is absent of Quakers, then no one needs to sail to England.” The Governor put his index finger to his mouth and curled it above his lower lip. He moved back to the window and gazed. He nodded his head and turned back to his aide. “Thy words ease my trepidation. But I must measure them further. Thou may take leave.” The Governor stared at the empty chair that Governor Winthrop had sat upon for many years. As he paced, he sensed the former Governor watching him. He stopped and stared back. “Ye New World that ye established on this hill is under siege,” he said. “We toil to keep it free of God’s vermin. But with Charles as our Sovereign, I fear we will be overrun with vermin. What will become of our common weal?” ***** This singular event had no direct effect on John Law. But it boded well for his future. Cromwell was dead, and a new king was on the English throne. The absolute control the Puritans had enjoyed under Lord Cromwell was weakening, which might create more tolerance for Scottish men, Quakers and any others who were not deemed God’s chosen ones. |

AuthorIn 2002, Alfred Woollacott, III retired from KPMG and began pursuing his family history. His research is meticulous and in December 2017, he began blogging about it, giving further insight to his novels Archives

August 2019

|

- Home

- About the Author

- Blog

-

"The Immigrant"

- Author's Interview

- Published Reviews of The Immigrant

- Resources for The Immigrant

- 3 September 1650 Dunbar Scotland

- November 1650 On the North Atlantic

- Early Winter 1650 - 1651 Charlestown, Massachusetts Bay Colony

- 22 April 1676 Concord, Massachusetts

- August 12, 1676 Miery Swamp Bristol, Rhode Island

- "The Believers"

- Other Timelines

-

Alfred's Four Legged Stool

- Eleven Generations of John Law Descendants

- John Law of Acton, Massachusetts

- Reuben Law of Acton, Massachusetts and Sharon, New Hampshire

- Re-dedication of Woollacott Square, 26 May 2015

- John Woollacott of Atherington, Devon, England, patriarch of the Fitchburg Woollacotts

- The Woollacotts of North Devon

- Early Woollacotts and Variations thereon

- Élisabeth Isabelle Salé, Les Fille du Roi

- Jill's four legged stool

RSS Feed

RSS Feed