This August, I re-experienced a Scottish experience while attending the Historical Novel Society Conference in Cumbernauld and visiting Dunbar and Durham – opening locations for “The Immigrant”. The conference was educational and entertaining and allowed time to network with others who had been only profile photos and social media posts.

Earlier, my wife and I attended the Royal Military Tattoo at Edinburgh Castle. Our seats were center front, below the Royal Box. Sitting in cool night air, the sideline bleachers created a tunnel that reverberated the ambiance toward us -- bagpipes, bugles, drums, fireworks, and “Amazing Grace” – a hymn I can’t hear without welling up. After the finale, an aroused throng propelled us down the Royal Mile as my wee bit of Scottish blood pulsated and filled my soul.

Earlier, my wife and I attended the Royal Military Tattoo at Edinburgh Castle. Our seats were center front, below the Royal Box. Sitting in cool night air, the sideline bleachers created a tunnel that reverberated the ambiance toward us -- bagpipes, bugles, drums, fireworks, and “Amazing Grace” – a hymn I can’t hear without welling up. After the finale, an aroused throng propelled us down the Royal Mile as my wee bit of Scottish blood pulsated and filled my soul.

Still cautious of left-side-of-the-road driving, I girded for a day trip to Durham and back. My nerves calmed once Garmin had navigated me through traffic, numerous roundabouts, and onto the motorway. Soon, a Dunbar road sign stirred me anew. Others aroused me further: Doon Hill, the novel’s opening scene; the Cocksburnpath, Cromwell’s potential break-out route south; and Morpeth, where foraging prisoners ate raw cabbage that poisoned their starved bodies. We were traveling the route my protagonist had traveled. We cruised in comfort; he had trekked the infamous “death march”.

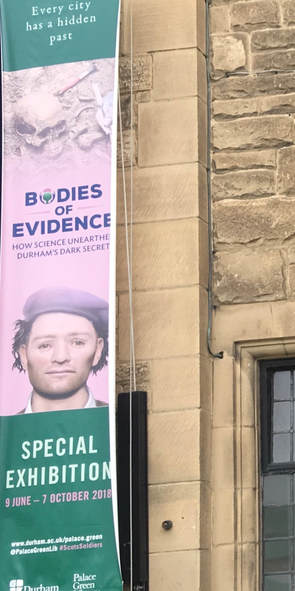

We arrived at Durham weary. Couldn’t imagine the prisoners’ exhaustion. Perhaps the fortunate ones were the fifteen hundred who died along the way. The Cathedral's towers pierced the ominous-looking, grey sky, appearing like a beacon to guide me. One canvas-wrapped tower was under repair. Inside, more repairs were occurring. Having stood for a near millennium, the Cathedral was worn, tired-looking, yet still magnificent. A sense of relief came while admiring its past glory. I had depicted it near-perfectly.

We arrived at Durham weary. Couldn’t imagine the prisoners’ exhaustion. Perhaps the fortunate ones were the fifteen hundred who died along the way. The Cathedral's towers pierced the ominous-looking, grey sky, appearing like a beacon to guide me. One canvas-wrapped tower was under repair. Inside, more repairs were occurring. Having stood for a near millennium, the Cathedral was worn, tired-looking, yet still magnificent. A sense of relief came while admiring its past glory. I had depicted it near-perfectly.

On our return, I saw the Doon Hill sign again and veered onto a rough-paved road, which turned into a cart path between open fields. We ascended, traveling on worn ruts while the centered grassy mound brushed and scraped the undercarriage, I was thankful when we finally plateaued. Dunbar lay below, undaunting, a seeming miniature village separating the North Sea from us. Winds blustered, but not as cold as they had been on 2 September 1650. I nodded my pleasure. The opening scene in “The Immigrant” had been described near-perfectly, too

“A fourteen-year-old John Law surveyed the hoof prints in the soggy ground and resumed his ascent of Doon Hill, the easternmost summit of Scotland’s Lammermuir Hills. He avoided the clumps and divots kicked up by the cavalry and reached a plateau. There, he stood among other pikemen while holding his pike erect. He looked down the slope and followed the Brox Burn as it slashed through the wooded glen and emptied into the Firth of Forth. On a sliver of flat land between the Doon Hill and the Firth was a salt-laden golf course, which was now occupied by Cromwell’s English Parliamentarian army. Behind the army, the Firth flowed into the seemingly endless North Sea. The masts of the English ships, which bobbed in a stiff breeze, were as tight as a comb’s teeth. John was initially frightened at the sight until he realized he was out of range of their cannons. As he thought further, he realized the English forces were a mile and a half away and had their backs to the sea. He was out of range of their cannons, too, and Cromwell’s options for movement were severely limited, which his young mind sensed was an advantage for the Scots.

He shifted his eyes further east and followed the Cocksburnpath, the main road south out of Dunbar to Berwick, England. The Scottish Royal troops were amassed on high ground, close to the road. East of the Coxsburnpath was a beach with Scottish forces on it and beyond them, the North Sea. An English retreat south seemed effectively blocked. In front of the road and nearer to John stood a few clusters of corn stalks on barren fields. John had heard the Scots had stripped the countryside bare ahead of the advancing English to limit their food supply. Now, he saw the effect of their destruction.

John rubbed his pale blues to ease the sting caused by salty mist being constantly driven into them. A gust fluttered his salt laden cheek fuzz, and he brushed at the tingle it created. Annoyed, he turned out of the wind, and his red locks flew from his neck and fluttered until the gust subsided. He surveyed his more immediate surroundings as the cold wind drove into his back. He was among Scottish cavalrymen, pikemen, musketeers, and a few dozen short-range cannons, which covered the hillside. He was heartened by the display of force. Scottish officers, a few garbed in black, many in scarlet with white-laced collars and cuffs trimmed with gold or silver laces, bounced in unison with their horses’ prance. Some wore blue woolen brimmed hats, and others donned steel helmets imported from the Continent. Their shoulder length hair flowed in the breeze. The officers were a spectacle of wealth that impressed John and increased his confidence.

John turned back toward the North Sea to face an endless gale. He tried to braid his hair, but it was useless. As he endured a lashing from snapping tresses, his mood soured. Me have failed me father so. He continued to dwell on his failure until the sun broke through the clouds and reflected off his pike. As the clouds pulled back, the endless wave of pikes, held erect by numb hands, created a rolling wave of brilliance that lit up Doon Hill. John’s mood brightened. He hoped the shock of radiance would blind the enemy below and terrify them into surrendering. But the clouds rolled back quickly, and a squall ensued. John wrapped his arms while struggling to hold his pike. He quivered until the rumble from a large blue flag with a white cross distracted him. ‘COVENANT for Religion Croune and Countrie’ rippled in the breeze, important words to the Covenanters, but still meaningless to John.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed