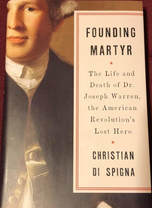

When I read a recent post about Christian Di Spagna’s book “Founding Martyr”, it reminded me of my intention to blog about Dr. Joseph Warren. In researching various historical figures for my current novel in progress, “The Patriot”, Warren’s life was so compelling I had to weave him into the novel. He was closely linked with those early disciples of the cause for independence -- John Hancock, Paul Revere, Samuel Adams, and others from the Sons of Liberty – and its first martyr.

He was born 11 June 1741 in Roxbury to Joseph and Mary (Stevens) Warren and attended the Roxbury Latin School, which was founded by Reverend John Eliot in 1645. Today, a statue of Warren's stands prominent on the School's grounds; the school is the oldest in continuous in North America. Obviously blessed with intellect, he enrolled in Harvard College where he studied medicine. At age 23, he married the heiress 18-year-old Elizabeth Hooten who bore him five children, four of whom lived before her death in 1772. In 1769, he became the Master of the Scottish Rite Freemasonry with Paul Revere being its Secretary; John Hancock succeeded Warren upon his death. No doubt, politics must have been discussed often while at the Freemason’s Lodge.

Dr. Warren never shrunk from the cause for independence as it sped toward its destiny and bloody beginning. In March 1775, despite death threats and amid heckling from British soldiers, Warren delivered an oratory honoring the victims of the Boston Massacre to a packed Old South Church. A month later, he was pivotal when ‘the shot was fired that was heard ‘round the world’. On 18 April, he sent Paul Revere and William Dawes on a midnight ride to warn Hancock and Adams who were in Lexington. The following day, he slipped out of Boston to participate in harassing the retreating British troops while administering to wounded rebels. A musket ball struck his wig during the conflict, and a day later his tear-filled mother pleaded with him not to risk his life. He responded, “Where danger is, dear mother, there must your son be. Now is no time for any of America's children to shrink from any hazard. I will set her free or die.”

In the ensuing two months, Warren recruited soldiers for the Colonist’s siege of Boston, enlisting more than 20,000 that forced him to garrison some in halls at Harvard College. On 14 June 1775, he was commissioned Major General of Massachusetts Militia. Three days later, he rushed to join his troops entrenched on Bunker Hill. Upon arriving, he asked Major General Israel Putnam where the heaviest fighting would be and entered the redoubt to where Putnam had just pointed. General Warren along with privates and others repelled two British advances before the third assault killed him.

For much more, I would suggest reading Di Spagna’s “Founding Martyr”.

In the ensuing two months, Warren recruited soldiers for the Colonist’s siege of Boston, enlisting more than 20,000 that forced him to garrison some in halls at Harvard College. On 14 June 1775, he was commissioned Major General of Massachusetts Militia. Three days later, he rushed to join his troops entrenched on Bunker Hill. Upon arriving, he asked Major General Israel Putnam where the heaviest fighting would be and entered the redoubt to where Putnam had just pointed. General Warren along with privates and others repelled two British advances before the third assault killed him.

For much more, I would suggest reading Di Spagna’s “Founding Martyr”.

In “The Patriot”, the novel’s protagonist Reuben Law had run out of powder and knew the time to flee was now. Once out of range of British muskets, he paused to witness the carnage below.

“Push on,” roared a voice in a British accent. The British had their bayonets lowered and were moving in for the kill.

Solomon and Reuben sprinted with others up the hill. When Reuben sensed he was out of musket range, he placed his hands on his thighs and panted. Solomon did, too. Where they had been two hundred pounding heartbeats earlier was overrun. The few who had remained fought to their death. Reuben was unsure if they had been heroic or foolish.

He straightened but continued to breathe deeply. Away from where Reuben had been, Colonel Prescott parried his ornamental saber with an enemy’s bayonet as he retreated. Soon, his attacker gave up the duel to join the surge toward another breastwork. Prescott scampered up the hill with his dust coat flowing behind him. He paused for a moment and, with arms akimbo, surveyed the battle below. He seemed to Reuben like a conquering hero.

At the breastwork to Reuben’s right, the patrician-looking man Reuben had noticed earlier lay dead. A musket ball had found his head, yet the British continued bayoneting him with a vengeance. They paused to strip off his expensive clothing. The erstwhile light-blue coat and satin waist-coat fringed in lace were crimson shreds. The bayoneting resumed and when they grew arm weary, they kicked him toward a shallow hole. He was disfigured beyond recognition, no longer seeming blue-blooded at all. He was foolish not to leave, thought Reuben. Why did he evoke such wrath from the British, he wondered?

The man Reuben pondered was Dr. Joseph Warren. He had served as President of Massachusetts Provincial Congress and, hours before his death, had been commissioned a Major General of Massachusetts Militia. To many British officers, Warren was the face of the rebellious cause. To Lieutenant James Drew his rage would turn to madness. Two days later, he would return to Bunker Hill and unearth Warren from his shallow grave to spit in his face, jump on his stomach, and cut off his head. Dr. Warren’s death was neither foolish nor heroic, but a martyrdom that would inspire the Colonists to never give up their revolutionary cause.

“Push on,” roared a voice in a British accent. The British had their bayonets lowered and were moving in for the kill.

Solomon and Reuben sprinted with others up the hill. When Reuben sensed he was out of musket range, he placed his hands on his thighs and panted. Solomon did, too. Where they had been two hundred pounding heartbeats earlier was overrun. The few who had remained fought to their death. Reuben was unsure if they had been heroic or foolish.

He straightened but continued to breathe deeply. Away from where Reuben had been, Colonel Prescott parried his ornamental saber with an enemy’s bayonet as he retreated. Soon, his attacker gave up the duel to join the surge toward another breastwork. Prescott scampered up the hill with his dust coat flowing behind him. He paused for a moment and, with arms akimbo, surveyed the battle below. He seemed to Reuben like a conquering hero.

At the breastwork to Reuben’s right, the patrician-looking man Reuben had noticed earlier lay dead. A musket ball had found his head, yet the British continued bayoneting him with a vengeance. They paused to strip off his expensive clothing. The erstwhile light-blue coat and satin waist-coat fringed in lace were crimson shreds. The bayoneting resumed and when they grew arm weary, they kicked him toward a shallow hole. He was disfigured beyond recognition, no longer seeming blue-blooded at all. He was foolish not to leave, thought Reuben. Why did he evoke such wrath from the British, he wondered?

The man Reuben pondered was Dr. Joseph Warren. He had served as President of Massachusetts Provincial Congress and, hours before his death, had been commissioned a Major General of Massachusetts Militia. To many British officers, Warren was the face of the rebellious cause. To Lieutenant James Drew his rage would turn to madness. Two days later, he would return to Bunker Hill and unearth Warren from his shallow grave to spit in his face, jump on his stomach, and cut off his head. Dr. Warren’s death was neither foolish nor heroic, but a martyrdom that would inspire the Colonists to never give up their revolutionary cause.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed