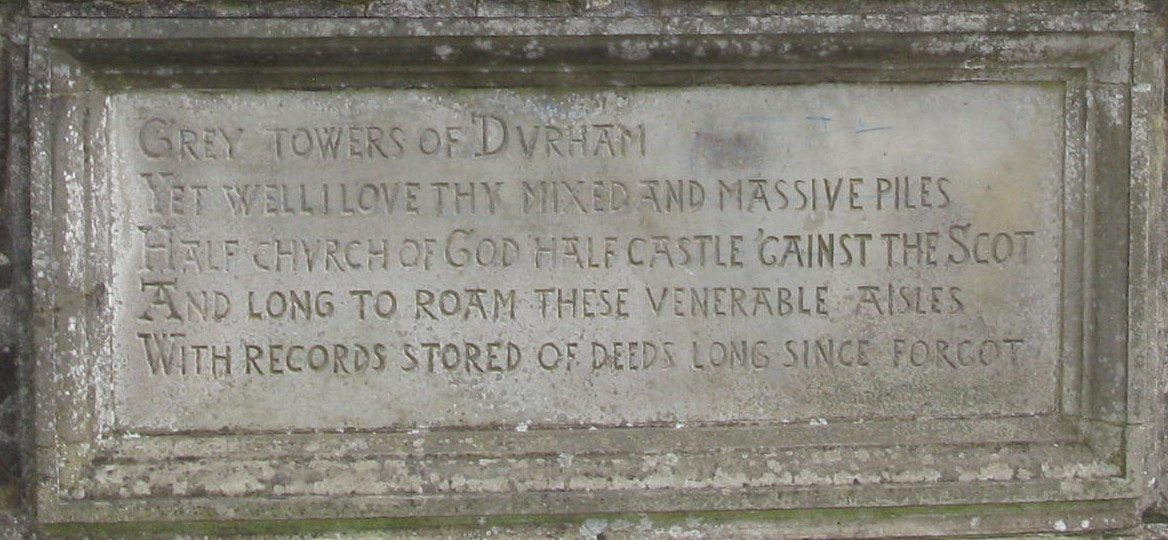

Durham Cathedral has stood for a near millennium as an example of advanced Norman Architecture for its time. The nave’s ribbed vault with pointed transverse arches supported on alternating slender composite piers and massive drum columns created an elaborate and complicated ground plan. The flying buttresses concealed within the triforium over the aisles allowed greater height, opening up wall space for larger windows. Situated on a promontory above the Wear River, the 217 foot central tower offers views of Durham and surrounding areas.

Nearby, the Bishop of Durham resided in Durham Castle. The bishopric had military as well as religious leadership and power until the 19th century. Among the Cathedral’s collections are St Cuthbert’s relics, the head of St Oswald of Northumbria, and the Venerable Bede’s remains; the library contains one of the most complete sets of early printed books in England, the pre-Dissolution monastic accounts, and three copies of Magna Carta.

The Cathedral has had a robust, glorious history except for the fall of 1650 when it achieved infamy. After the 3 September 1650 Battle of Dunbar, it became a makeshift prison for Scottish prisoners-of-war. Some 5,000 endured a ‘death march’ from Dunbar to Durham. Only 3,000 survived and arrived at the Cathedral to suffer more inhumanity, living largely without food, water, or heat. The prisoners destroyed much of the cathedral woodwork for firewood. Some 1,700 died while there and were buried in mass graves about the grounds.

The Cathedral has had a robust, glorious history except for the fall of 1650 when it achieved infamy. After the 3 September 1650 Battle of Dunbar, it became a makeshift prison for Scottish prisoners-of-war. Some 5,000 endured a ‘death march’ from Dunbar to Durham. Only 3,000 survived and arrived at the Cathedral to suffer more inhumanity, living largely without food, water, or heat. The prisoners destroyed much of the cathedral woodwork for firewood. Some 1,700 died while there and were buried in mass graves about the grounds.

In “The Immigrant”, fourteen year old John Law survived his Durham ordeal to face another — a horrific, life transforming, trans-Atlantic crossing to the Colonies. Here is a day in his life:

Durham Cathedral, Durham, England

Autumn 1650

As John lay on the Durham Cathedral floor, a speck beneath the towering Norman-styled arches, he pondered. Andrew Wright had been dead-on correct again. The English only took the healthy, and now John knew why. The sickliest of the more than 5,000 prisoners had perished on the eight day, 120 mile ‘death march’ from Dunbar, Scotland to Durham, England. Andrew Wright was still in Scotland, perhaps with his clan, and John was further from his mother. Maybe John had been less fortunate than he thought. Maybe the truly blessed ones were the 2,000 prisoners who littered a southern road into England.

John lowered his melancholy eyelids, and when they reopened, he contemplated the designs on the arches. His usual worship place was Spartan by comparison. Even the church, which his father insisted John attend the year before he died, couldn’t compare to this magnificent mammoth structure. The walk to that Scottish church was cold and lengthy, and John complained constantly. But his father was resolute; John needed to witness what his father had witnessed as lad. As John reminisced, he appreciated his father’s insistence.

That church was candlelit, insufficient to heat its stone structure, but sufficient to warm John’s heart. The cleric’s robe swooshed as he moved about the altar. An organ shattered the stillness, and the congregation sang. The shivers, which John had then, returned. He inched close to his mother since her sweet warble was more appealing than his father’s off-key monotone. Her mouth and lips changed with each syllable, and when she smiled at him while singing, his body prickled. The walk home was neither cold nor lengthy, but silent, except for crunching feet on the meadow’s rime and his mother’s hum of a previously sung hymn.

Durham Cathedral’s stench grew overwhelming, and John ceased daydreaming. Vomit and urine splotches, excrement in nooks, doses of rotting bodies and traces of disease from those waiting to die created a noxious concoction. Even Durham Cathedral’s towering arches were insufficient to allow the stench to dissipate. John wiggled his nose and rolled to his side. One stained glass window still remained intact. Jesus, with inviting open palms hanging at his side, stared back. John had prayed to that window, but God hadn’t hear him. He glared at Jesus and thought about praying again, but he rolled away and became captive to the nave’s ribbed arches that formed part of the Cathedral’s vault.

As twilight came, the predictable feeding clamor ensued and distracted John. He arose and noticed a desperate, thin, and seemingly familiar wretch, pleading with a guard. Coins fell into a guard’s open palm, bread was handed over, and the wretch backed away. John’s memory was finally triggered. It be MacTavish. But he nae be a fat bastard.

He wondered if God had rendered justice after all. MacTavish, the swine, ate his fill at Dunbar, and the English probably mistook him as hearty. Now, he grovels for swill and is forced to live in this hell with the rest of us. John smiled as his eyes rose up the arches and through the ceiling. He nodded a ‘thank you’ to God. But God didn’t acknowledge it. Only Andrew’s earlier words echoed down from the arches. “MacTavish’s coins will pay for safe passage after Cromwell prevails.”

John whirled to the stained glass window of Jesus, but he couldn’t maintain eye contact with him. He thought further as MacTavish moved out of the nave toward the choir section, before disappearing into the darkened recesses of the aisle on the south side. As John waited for his food, Malcolm’s previous boast throbbed in his temples. “Me will slay MacTavish and take his coins.” The words continued to resonate while John ate.

When John finished eating, he moved toward the choir section. When he caught a glimpse of Jesus, he moved back to the nave. He sprawled onto the stone floor, allowing the Cathedral’s drone to be his lullaby as he tried to sleep. Unlike his mother’s soothing tones, this lullaby was a jumble of scuffles, raised voices, thumps and howls, which dimmed to murmurs. But this night, a persistent thought accompanied the lullaby. Slay MacTavish and take his coins for safe passage home.

John couldn’t sleep, and he arose and drifted toward the darkness again, unsure of what he would do. A broken, jagged-edge spindle from the altar rail lay on the floor of the choir section. It seemed to beckon, and John grabbed it and held it like a dagger. He moved to the darkened recesses near the small arches that formed the aisle of the choir section’s south side. Using the aisle’s outer wall for bearings, he stepped further away from the nave while searching for MacTavish. When he saw a silhouette of a man just ahead, his heart raced as his vision blurred. MacTavish? Propped against that column?

MacTavish’s ashen cheeks were noticeable in the darkness and seemingly summoning John. He raised the altar spindle and took deliberate steps. As he drew closer, John noticed MacTavish’s eyes were opened, and he held his last step in mid-air. His thigh began to quiver. Me God, does he see me? John lowered his leg slowly. MacTavish hadn’t noticed.

He inhaled while contemplating his next step, still unsure . . .

Durham Cathedral, Durham, England

Autumn 1650

As John lay on the Durham Cathedral floor, a speck beneath the towering Norman-styled arches, he pondered. Andrew Wright had been dead-on correct again. The English only took the healthy, and now John knew why. The sickliest of the more than 5,000 prisoners had perished on the eight day, 120 mile ‘death march’ from Dunbar, Scotland to Durham, England. Andrew Wright was still in Scotland, perhaps with his clan, and John was further from his mother. Maybe John had been less fortunate than he thought. Maybe the truly blessed ones were the 2,000 prisoners who littered a southern road into England.

John lowered his melancholy eyelids, and when they reopened, he contemplated the designs on the arches. His usual worship place was Spartan by comparison. Even the church, which his father insisted John attend the year before he died, couldn’t compare to this magnificent mammoth structure. The walk to that Scottish church was cold and lengthy, and John complained constantly. But his father was resolute; John needed to witness what his father had witnessed as lad. As John reminisced, he appreciated his father’s insistence.

That church was candlelit, insufficient to heat its stone structure, but sufficient to warm John’s heart. The cleric’s robe swooshed as he moved about the altar. An organ shattered the stillness, and the congregation sang. The shivers, which John had then, returned. He inched close to his mother since her sweet warble was more appealing than his father’s off-key monotone. Her mouth and lips changed with each syllable, and when she smiled at him while singing, his body prickled. The walk home was neither cold nor lengthy, but silent, except for crunching feet on the meadow’s rime and his mother’s hum of a previously sung hymn.

Durham Cathedral’s stench grew overwhelming, and John ceased daydreaming. Vomit and urine splotches, excrement in nooks, doses of rotting bodies and traces of disease from those waiting to die created a noxious concoction. Even Durham Cathedral’s towering arches were insufficient to allow the stench to dissipate. John wiggled his nose and rolled to his side. One stained glass window still remained intact. Jesus, with inviting open palms hanging at his side, stared back. John had prayed to that window, but God hadn’t hear him. He glared at Jesus and thought about praying again, but he rolled away and became captive to the nave’s ribbed arches that formed part of the Cathedral’s vault.

As twilight came, the predictable feeding clamor ensued and distracted John. He arose and noticed a desperate, thin, and seemingly familiar wretch, pleading with a guard. Coins fell into a guard’s open palm, bread was handed over, and the wretch backed away. John’s memory was finally triggered. It be MacTavish. But he nae be a fat bastard.

He wondered if God had rendered justice after all. MacTavish, the swine, ate his fill at Dunbar, and the English probably mistook him as hearty. Now, he grovels for swill and is forced to live in this hell with the rest of us. John smiled as his eyes rose up the arches and through the ceiling. He nodded a ‘thank you’ to God. But God didn’t acknowledge it. Only Andrew’s earlier words echoed down from the arches. “MacTavish’s coins will pay for safe passage after Cromwell prevails.”

John whirled to the stained glass window of Jesus, but he couldn’t maintain eye contact with him. He thought further as MacTavish moved out of the nave toward the choir section, before disappearing into the darkened recesses of the aisle on the south side. As John waited for his food, Malcolm’s previous boast throbbed in his temples. “Me will slay MacTavish and take his coins.” The words continued to resonate while John ate.

When John finished eating, he moved toward the choir section. When he caught a glimpse of Jesus, he moved back to the nave. He sprawled onto the stone floor, allowing the Cathedral’s drone to be his lullaby as he tried to sleep. Unlike his mother’s soothing tones, this lullaby was a jumble of scuffles, raised voices, thumps and howls, which dimmed to murmurs. But this night, a persistent thought accompanied the lullaby. Slay MacTavish and take his coins for safe passage home.

John couldn’t sleep, and he arose and drifted toward the darkness again, unsure of what he would do. A broken, jagged-edge spindle from the altar rail lay on the floor of the choir section. It seemed to beckon, and John grabbed it and held it like a dagger. He moved to the darkened recesses near the small arches that formed the aisle of the choir section’s south side. Using the aisle’s outer wall for bearings, he stepped further away from the nave while searching for MacTavish. When he saw a silhouette of a man just ahead, his heart raced as his vision blurred. MacTavish? Propped against that column?

MacTavish’s ashen cheeks were noticeable in the darkness and seemingly summoning John. He raised the altar spindle and took deliberate steps. As he drew closer, John noticed MacTavish’s eyes were opened, and he held his last step in mid-air. His thigh began to quiver. Me God, does he see me? John lowered his leg slowly. MacTavish hadn’t noticed.

He inhaled while contemplating his next step, still unsure . . .

RSS Feed

RSS Feed