In the ensuing two months, Warren recruited soldiers for the Colonist’s siege of Boston, enlisting more than 20,000 that forced him to garrison some in halls at Harvard College. On 14 June 1775, he was commissioned Major General of Massachusetts Militia. Three days later, he rushed to join his troops entrenched on Bunker Hill. Upon arriving, he asked Major General Israel Putnam where the heaviest fighting would be and entered the redoubt to where Putnam had just pointed. General Warren along with privates and others repelled two British advances before the third assault killed him.

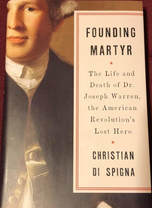

For much more, I would suggest reading Di Spagna’s “Founding Martyr”.

“Push on,” roared a voice in a British accent. The British had their bayonets lowered and were moving in for the kill.

Solomon and Reuben sprinted with others up the hill. When Reuben sensed he was out of musket range, he placed his hands on his thighs and panted. Solomon did, too. Where they had been two hundred pounding heartbeats earlier was overrun. The few who had remained fought to their death. Reuben was unsure if they had been heroic or foolish.

He straightened but continued to breathe deeply. Away from where Reuben had been, Colonel Prescott parried his ornamental saber with an enemy’s bayonet as he retreated. Soon, his attacker gave up the duel to join the surge toward another breastwork. Prescott scampered up the hill with his dust coat flowing behind him. He paused for a moment and, with arms akimbo, surveyed the battle below. He seemed to Reuben like a conquering hero.

At the breastwork to Reuben’s right, the patrician-looking man Reuben had noticed earlier lay dead. A musket ball had found his head, yet the British continued bayoneting him with a vengeance. They paused to strip off his expensive clothing. The erstwhile light-blue coat and satin waist-coat fringed in lace were crimson shreds. The bayoneting resumed and when they grew arm weary, they kicked him toward a shallow hole. He was disfigured beyond recognition, no longer seeming blue-blooded at all. He was foolish not to leave, thought Reuben. Why did he evoke such wrath from the British, he wondered?

The man Reuben pondered was Dr. Joseph Warren. He had served as President of Massachusetts Provincial Congress and, hours before his death, had been commissioned a Major General of Massachusetts Militia. To many British officers, Warren was the face of the rebellious cause. To Lieutenant James Drew his rage would turn to madness. Two days later, he would return to Bunker Hill and unearth Warren from his shallow grave to spit in his face, jump on his stomach, and cut off his head. Dr. Warren’s death was neither foolish nor heroic, but a martyrdom that would inspire the Colonists to never give up their revolutionary cause.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed