Hammersmith, the Saugus Ironworks, was Governor Winthrop’s second venture into manufacturing iron goods locally as oppose to importing them from England. Replacing the failed Braintree operations, Hammersmith began operations in 1646, north of Boston, eventually became a technologically advanced operation that produced one ton of cast iron per day. The blast furnace produced pig iron and grey iron for pots, pans, and skillets. The forge refined the pig iron into wrought iron. A five hundred pound hammer made merchant bars for blacksmiths who turned them into finished product. A rolling and slitting mill manufactured nails, bolts, horse shoes, wagon tires, axes, saw blades, and other tools.

Initially, skilled labor came from England, and after the Battle of Dunbar on 3 September 1650, a cheap source of labor arrived, indentured Scottish POWs. Unskilled, these indentured encountered frequent accidents, especially around the hammer and forge; some were fatal. After work hours, some were often arrested for drunkenness, adultery, gambling, fighting, cursing, not attending church, and wearing fine clothes -- an anathema to the Puritan Theocracy. After three to as high as seven years, the Scots were freed from their indenture to begin assimilating into society.

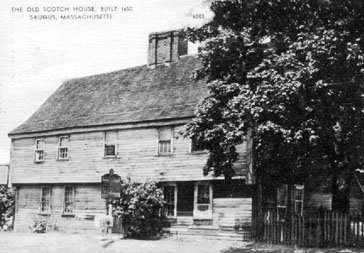

Samuel Bennett, a master carpenter, came to the Colonies in 1635 and received a grant of twenty acres in Lynn. He often appeared in court and was described once as “the verryest rascoll in New England”. Nonetheless, he acquired land, built housing, and prospered. In 1651, he built a boarding house for the indentured Scots not far from Hammersmith. His two storied ‘Scotch House’ had a centered chimney with an oven and open areas either side of it for eating and sleeping. The Scots slept two to a bed in the eleven available beds.

Today, the restored Saugus Ironworks is a National Historic Site, which I visited for background research for “The Immigrant”. The book’s protagonist, John Law, spent his few years in the Colonies at the Ironworks. But, his fate was cast before he arrived. In 1650, Richard Leader ceased managing Hammersmith having been replaced by John Gifford and William Awbrey. Undaunted, he sailed to London to meet with the Ironworks chief financial backer, John Becx. Here is that scene from “The Immigrant” that set in motion events that changed young John Law’s life forever.

* * * * *

Outside the heavy, chocolate-colored door to John Becx’s well-appointed office in London’s financial district, Richard Leader paced while clutching his documents. Richard had been in charge of the Braintree Ironworks operation in the Colonies, as agent for the Ironworks’ financial investors. By 1647, the Braintree operation was failing, and Richard found another location on behalf of the investors, north of Braintree on the Saugus River. He had been instrumental in getting the Saugus site built and operational, yet the investors lost faith in him. John Becx, a resident of London and a wealthy industrialist, was the lead investor for the twenty-four who financed the Ironworks. Richard had left the Colonies in the summer to meet with Becx in England.

One of Becx’s aides opened the door, and Richard hurried into the office. Becx sat between heavy wooden supports for his over-sized desk. The legs of the diminutive Becx dangled from the leather-padded chair just above the floor. He ceased swinging them back and forth and said, “Richard, I provided the financing for the Ironworks, and my decision is final. John Gifford and William Awbrey are replacing you.”

Richard raised a hand to stop Becx from saying more. “I come not to ask thee to reconsider,” he said.

“Wise on your part,” said Becx as he slid off his chair to pace. “I respect your engineering talents. You built a magnificent ironworks, yet we still lost money.” He ceased pacing and turned to Richard. “What happened?”

Richard squirmed. “Magnificent truly, but we lacked sufficient labor.”

“How can that be?” asked Becx. “Governor John Winthrop was keen on our venture. Said it was important to his common weal. His son oversaw everything until you replaced him.” Becx’s eyes widened. “Aha, was it spite?”

“Perhaps, it was spite.” Becx frowned, and Richard quickly continued. “No matter, the Governor is deceased, and John the younger is in Connecticut. The Winthrops will no longer interfere.”

“Splendid, the situation is improved. Gifford and Awbrey will turn a profit.”

“Doubtful, the problem is bigger than the Winthrops. It’s that damn colony.”

Becx raised his head, seemingly wanting to learn more.

“The men are clergy, or artisans, or farmers, and the rest are their goodwives and children. The Ironworks never had enough labor.”

“Then we should have imported some laborers,” said Becx.

“Impossible. The Governor determined who would leave England for his colony. He oversaw every ship that arrived and sent back the ones not to his liking.” Becx glared his skepticism and Richard added, “Well not every ship. Thou art a Dutchman, ye understand.”

Becx smiled briefly and said, “But you still hired laborers.”

“We trained a few yeomen. But we needed colliers, furnace men, and…”

“You should have trained more yeomen,” interrupted Becx.

“There are not enough men to train. Even so, it is a dear wage we pay. And force them to deliver a fair day’s work, why the constable, clergy, the whole town are upon thee.”

Becx sighed. “I’ve read the court proceedings and paid the fines.”

“They are all kin. It’s never a fair court.”

“Less dear labor,” said Becx as he paced while pondering. “We need to reduce our costs.” He stopped and turned to Richard. “How about the natives?”

Richard sneered. “With sincerest respects.”

“Just a thought,” said Becx as he rubbed his chin. “Still a few ships with cheap labor could solve our problem.”

“Governor Endicott would never allow it.”

“Nonsense. A few ships will not spoil that new world experiment.”

“But if he does object, what becomes of these undesirables?” asked Richard.

“The Governor can determine their fate.” Becx pondered further and a smile crossed his face. He gave a concluding head nod and turned back to Richard. “Now, what’s your purpose today?”

“A saw mill in the colonies,” said Richard as he laid out his documents. “Thou will make a fortune.”

“And is Governor Endicott keen on this venture?”

“The mill will be north of the Massachusetts colony, on the Piscataqua River.”

“I like that,” said Becx as his smile broadened.

“There is plenty of timber hither,” said Richard as he pointed to a spot on his map, “with a river to the sea. It’s ideal.”

“And labor?”

“It will be dear, but worth it.” Richard picked up his other documents. “I have computed the labor costs in these journals.”

Becx grabbed the documents from Richard. “I admire your engineering skills, but you are not a financial man. I must study them further. Adieu Richard Leader.”

As Richard turned to leave, Becx said, “You know Richard, if the Governor protests too much about undesirables in his Massachusetts, we could send them north.”

“Be assured,” said Richard as he paused at the door, “he will protest.”

* * * * *

Outside the heavy, chocolate-colored door to John Becx’s well-appointed office in London’s financial district, Richard Leader paced while clutching his documents. Richard had been in charge of the Braintree Ironworks operation in the Colonies, as agent for the Ironworks’ financial investors. By 1647, the Braintree operation was failing, and Richard found another location on behalf of the investors, north of Braintree on the Saugus River. He had been instrumental in getting the Saugus site built and operational, yet the investors lost faith in him. John Becx, a resident of London and a wealthy industrialist, was the lead investor for the twenty-four who financed the Ironworks. Richard had left the Colonies in the summer to meet with Becx in England.

One of Becx’s aides opened the door, and Richard hurried into the office. Becx sat between heavy wooden supports for his over-sized desk. The legs of the diminutive Becx dangled from the leather-padded chair just above the floor. He ceased swinging them back and forth and said, “Richard, I provided the financing for the Ironworks, and my decision is final. John Gifford and William Awbrey are replacing you.”

Richard raised a hand to stop Becx from saying more. “I come not to ask thee to reconsider,” he said.

“Wise on your part,” said Becx as he slid off his chair to pace. “I respect your engineering talents. You built a magnificent ironworks, yet we still lost money.” He ceased pacing and turned to Richard. “What happened?”

Richard squirmed. “Magnificent truly, but we lacked sufficient labor.”

“How can that be?” asked Becx. “Governor John Winthrop was keen on our venture. Said it was important to his common weal. His son oversaw everything until you replaced him.” Becx’s eyes widened. “Aha, was it spite?”

“Perhaps, it was spite.” Becx frowned, and Richard quickly continued. “No matter, the Governor is deceased, and John the younger is in Connecticut. The Winthrops will no longer interfere.”

“Splendid, the situation is improved. Gifford and Awbrey will turn a profit.”

“Doubtful, the problem is bigger than the Winthrops. It’s that damn colony.”

Becx raised his head, seemingly wanting to learn more.

“The men are clergy, or artisans, or farmers, and the rest are their goodwives and children. The Ironworks never had enough labor.”

“Then we should have imported some laborers,” said Becx.

“Impossible. The Governor determined who would leave England for his colony. He oversaw every ship that arrived and sent back the ones not to his liking.” Becx glared his skepticism and Richard added, “Well not every ship. Thou art a Dutchman, ye understand.”

Becx smiled briefly and said, “But you still hired laborers.”

“We trained a few yeomen. But we needed colliers, furnace men, and…”

“You should have trained more yeomen,” interrupted Becx.

“There are not enough men to train. Even so, it is a dear wage we pay. And force them to deliver a fair day’s work, why the constable, clergy, the whole town are upon thee.”

Becx sighed. “I’ve read the court proceedings and paid the fines.”

“They are all kin. It’s never a fair court.”

“Less dear labor,” said Becx as he paced while pondering. “We need to reduce our costs.” He stopped and turned to Richard. “How about the natives?”

Richard sneered. “With sincerest respects.”

“Just a thought,” said Becx as he rubbed his chin. “Still a few ships with cheap labor could solve our problem.”

“Governor Endicott would never allow it.”

“Nonsense. A few ships will not spoil that new world experiment.”

“But if he does object, what becomes of these undesirables?” asked Richard.

“The Governor can determine their fate.” Becx pondered further and a smile crossed his face. He gave a concluding head nod and turned back to Richard. “Now, what’s your purpose today?”

“A saw mill in the colonies,” said Richard as he laid out his documents. “Thou will make a fortune.”

“And is Governor Endicott keen on this venture?”

“The mill will be north of the Massachusetts colony, on the Piscataqua River.”

“I like that,” said Becx as his smile broadened.

“There is plenty of timber hither,” said Richard as he pointed to a spot on his map, “with a river to the sea. It’s ideal.”

“And labor?”

“It will be dear, but worth it.” Richard picked up his other documents. “I have computed the labor costs in these journals.”

Becx grabbed the documents from Richard. “I admire your engineering skills, but you are not a financial man. I must study them further. Adieu Richard Leader.”

As Richard turned to leave, Becx said, “You know Richard, if the Governor protests too much about undesirables in his Massachusetts, we could send them north.”

“Be assured,” said Richard as he paused at the door, “he will protest.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed