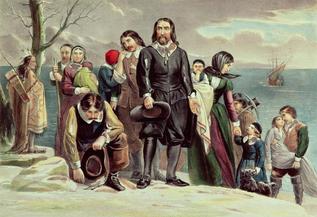

The Great Migration (1630 - 1640) consisted of twenty thousand, primary English immigrants trekking to a new world in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. This wave was ground zero, a beginning for what would eventually become America. They dealt with the indigenous people in various way to claim the land and built for themselves a Puritan Theocracy, free of diversity.

For a decade the Puritans had their way until another wave, perhaps more appropriately, a trickle of Scottish Prisoners of War arrived in 1651 — Immigration 1.0. These invaders of an erstwhile virgin land spoke differently with a Scottish burr, were Presbyterians not Puritans, and worst of all had fought against the Puritans’ guardian, their beloved Oliver Cromwell. To some, they were the enemy, and to others, a cheap source of labor for the Saugus Iron Works. The Great Migration had consisted of family units often bound by kindred ties or by residing previously in the same English village. These Scots were young males, rowdy, and lacking the discipline that marriage and a family require.

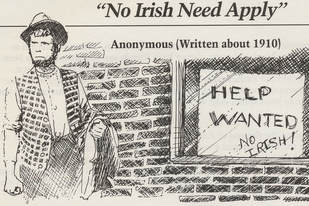

Later, French Canadians streamed down from Quebec, cheap labor to work the textile mills along the Merrimack River in Manchester, NH, and Lowell and Lawrence, Mass. By the mid-twentieth century, French-Canadian Americans comprised thirty percent of Maine, and towns like Lewiston had their enclaves known as “Little Canada”.

Similarly, at the turn of the last century Italians arrived, congregating in an enclave in Boston’s North End. Like the waves before, they faced challenges - poverty, discrimination, and a language barrier. They were full of emotion and more swarthy than the reserved, pale Yankee Puritans who were Boston’s establishment, seemingly under siege.

And the waves continue. Today, Hispanics and Muslims are in the news. Even on this tiny island of Martha’s Vineyard, we have a significant minority of Brazilians. Some come seeking jobs and, as a source of cheap labor, their opportunities abound. They seek a new start, some seek asylum. They speak different languages, and certain groups are viewed by some Americans as terrorist, the enemy similar to the view some Puritans had of the Scottish Prisoners of War who arrived 367 years earlier.

The more things change, the more they stay the same. Did John Law face greater discrimination than subsequent immigration waves would face? And how about today’s immigrants? If you read The Immigrant, you might find some answers to these questions.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed