Marie was born about 1635 in the diocese of Meaux in the Brie region of Champagne. After her father’s death, she left for New France and eventually married Louis Jobidon in Québec City in the home of Guillaume Thibaut. No written marriage contract has been found possibly since neither spouse could sign their name. Marie and Louis had eleven children over a period of twenty years. Several were born in primitive quarters during the harsh Québec winters, three died young, and one was mentally challenged. Louis died in Château-Richer in 1677, a year after the baptism of his eleventh child. Marie raised the children as a widow until she married Julien Allard. He had been widowed years earlier and left for New France in 1665 alone. He and Marie had no children. Marie died 24 December 1696 and was buried at Château-Richer.

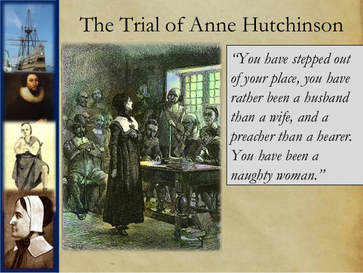

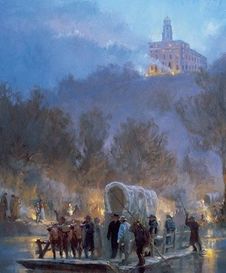

The majority of the filles came from Paris, Normandy, and the western regions of France. Their social backgrounds differed, yet all were poor. Many were orphans with low literacy levels. Some came from noble families that had lost their fortunes, and others from large families with a daughter to ‘spare’. The filles disembarked at Québec City, Trois-Rivières, and Montreal. Most often the couples were engaged in a church with their priests as their witnesses. A marriage contract was signed and notarized to protect the women giving them financial security if anything happened to them or their husbands and the freedom to annul the contract should the husband prove incompatible. Some eight hundred filles arrived from 1663 to 1673, and Pierre J. Gagné has written a brief biography of each. Mon Fille du Roi is Élisabeth Salé, my seven-greats grandmother.

Jacques and Élisabeth resided first at Trois-Rivières where their first two sons were baptized before settling at Neuville/Les Écureuils. Later, the family moved to Cap-Santé and settled on lot hundred and five of the new division. They would have fourteen children with many reaching adulthood. They had done their small part for their king, populate New France. Jacques died about 1718. Élisabeth died on 31 December 1722 and was buried at Cap-Santé

RSS Feed

RSS Feed