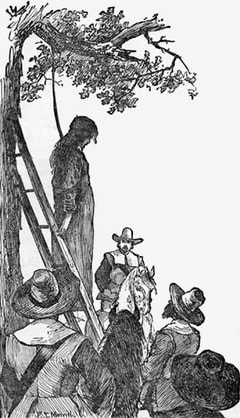

The 1630 - 1640 great migration was fueled in large part by those seeking religious freedom. These emigres, unified in faith and settled far from home, over time created a Puritan Theocracy. Ironically, the emigrants had fled religious persecution only to become oppressors; they were most spiteful toward the Quakers. On 27 October 1659, Quakers William Robinson, Marmaduke Stephenson, and Mary Dyer were scheduled to be hanged in Boston. Each climbed the ladder, and a noose hanging from an elm tree was tightened around each’s neck. William went first, followed by Marmaduke, and each died once the ladder was removed. Mary, with hands and legs bound and a handkerchief covering her face waited on the ladder. However, her life was spared by a last minute reprieve.  Some twenty years earlier, Mary gave birth to a deformed stillborn. Realizing the theological implications, she concealed the circumstances of her birth and buried the child secretly. Once Governor Winthrop learned of the situation, he investigated further and unearthed Mary’s secret. The Governor believed Mary’s monstrous birth was further proof of God’s disapproval of her antinomian heretics. She fled Massachusetts for Rhode Island to join Anne Hutchinson, Roger Williams, and other persecuted exiles. Later, Mary returned to England and became inspired by George Fox and his Society of Friends. She returned to Boston in 1657. The day after her reprieve, Mary wrote to the General Court refusing to accept her pardon's terms. While the General Court attempted to soften the terms, Mary left for Rhode Island again, only to return in the spring of 1660. She was resolute; either the authorities would change their laws or they would need to hang a woman. On 1 June 1660, she was led to the gallows and given the opportunity to recant her beliefs. "Nay, I cannot;” said Mary, “for in obedience to the will of the Lord God I came, and in his will I abide faithful to the death." The ladder was removed, and she died soon thereafter.  William Leddra, the fourth of the Boston Martyrs, like the others was pure of character. Even so, he endured beatings and banishment for preaching in Massachusetts. When he defied his banishment and returned in 1660, he was arrested, charged with sympathizing with the Quakers who were executed before him, refusing to remove his hat, and using "thee" and "thou" to imply equality of all people. Imprisoned, he lay chained to a log throughout the winter without heat. In a dark cell before being led to his gallows on 24 March 1661, he wrote to his wife. Standing beneath the elm with arms tied while a noose swayed in the breeze, he said, "For bearing my testimony for the Lord against deceivers and the deceived, I am brought here to suffer." His last words were, "Lord Jesus, receive my spirit." The martyrdom created an outrage throughout the colony, which eventually reached England. In September 1661, the king directed that all legal actions against the Quaker cease. Did the king's order suppress the theocratic zeal? Perhaps. Here is a relevant scene from “The Immigrant” November 1661 Governor’s Chambers, Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony “I fear ye hangings of Mary Dyer and William Leddra have returned to haunt us,” said the Governor’s aide. “Those Quakers were hung in Boston Common by order of ye Great Court of ye Commonwealth,” said Governor Endicott. “Why dost thee have dread-filled thoughts now?” “Samuel Shattuck hath returned with a message,” said the aide. “A message from that banished Quaker hath no meaning in ye Commonwealth.” “Governor, the message hath been scribed on parchment and hath a seal.” The Governor moved to the window and looked out at the graying skies. He grimaced and turned back. “Allow ye Quaker into my chamber.” The door opened, and a plainly dressed man with a wide brim hat entered, holding a sealed parchment. He lowered his head to the Governor. “How dare thee show disrespect for thy Governor?” said the aide. Shattuck cowered as the aide grabbed the crown of his hat and yanked it off of his head. The aide placed the crumbled hat on the desk, took the parchment, and handed it to the Governor. The Governor broke the seal, and his eyes shifted to the signature and seal at the bottom. He dropped his hand that held the parchment to his side and removed his hat with his other hand. “It’s from His Royal Majesty, Charles II,” said the Governor as he bowed his head. He held the parchment up, squinted, and moved to the window for more light. An anxious aide and a now less concerned Shattuck watched the straight-faced Governor. “We shall obey as thy Majesty commands,” said the Governor. “Thou may take leave, Samuel Shattuck.” Once the door shut, the Governor tightened his grip on the parchment and turned to his aide. “Summon the magistrates and ministers forthwith.” “And what shall I say to them?” “Tell them His Majesty commands jailed Quakers, from this day forth, will be tried on English soil.” The aide bowed his head. “Very well, as thou command.” “To the contrary, it is quite unwell. Once in England, ye Quakers will bear nothing but false witness against our Commonwealth justice, prevaricating dogs to amuse our Sovereign.” “Then let ye dogs roam and howl in the Commonwealth and not whimper at the foot of our Sovereign,” said the aide. “Shall I fetch William Sutton, ye Boston jailer?” “Pray tell, why?” “If ye jail is absent of Quakers, then no one needs to sail to England.” The Governor put his index finger to his mouth and curled it above his lower lip. He moved back to the window and gazed. He nodded his head and turned back to his aide. “Thy words ease my trepidation. But I must measure them further. Thou may take leave.” The Governor stared at the empty chair that Governor Winthrop had sat upon for many years. As he paced, he sensed the former Governor watching him. He stopped and stared back. “Ye New World that ye established on this hill is under siege,” he said. “We toil to keep it free of God’s vermin. But with Charles as our Sovereign, I fear we will be overrun with vermin. What will become of our common weal?” ***** This singular event had no direct effect on John Law. But it boded well for his future. Cromwell was dead, and a new king was on the English throne. The absolute control the Puritans had enjoyed under Lord Cromwell was weakening, which might create more tolerance for Scottish men, Quakers and any others who were not deemed God’s chosen ones.  Hammersmith, the Saugus Ironworks, was Governor Winthrop’s second venture into manufacturing iron goods locally as oppose to importing them from England. Replacing the failed Braintree operations, Hammersmith began operations in 1646, north of Boston, eventually became a technologically advanced operation that produced one ton of cast iron per day. The blast furnace produced pig iron and grey iron for pots, pans, and skillets. The forge refined the pig iron into wrought iron. A five hundred pound hammer made merchant bars for blacksmiths who turned them into finished product. A rolling and slitting mill manufactured nails, bolts, horse shoes, wagon tires, axes, saw blades, and other tools.  Initially, skilled labor came from England, and after the Battle of Dunbar on 3 September 1650, a cheap source of labor arrived, indentured Scottish POWs. Unskilled, these indentured encountered frequent accidents, especially around the hammer and forge; some were fatal. After work hours, some were often arrested for drunkenness, adultery, gambling, fighting, cursing, not attending church, and wearing fine clothes -- an anathema to the Puritan Theocracy. After three to as high as seven years, the Scots were freed from their indenture to begin assimilating into society.  Samuel Bennett, a master carpenter, came to the Colonies in 1635 and received a grant of twenty acres in Lynn. He often appeared in court and was described once as “the verryest rascoll in New England”. Nonetheless, he acquired land, built housing, and prospered. In 1651, he built a boarding house for the indentured Scots not far from Hammersmith. His two storied ‘Scotch House’ had a centered chimney with an oven and open areas either side of it for eating and sleeping. The Scots slept two to a bed in the eleven available beds. Today, the restored Saugus Ironworks is a National Historic Site, which I visited for background research for “The Immigrant”. The book’s protagonist, John Law, spent his few years in the Colonies at the Ironworks. But, his fate was cast before he arrived. In 1650, Richard Leader ceased managing Hammersmith having been replaced by John Gifford and William Awbrey. Undaunted, he sailed to London to meet with the Ironworks chief financial backer, John Becx. Here is that scene from “The Immigrant” that set in motion events that changed young John Law’s life forever.

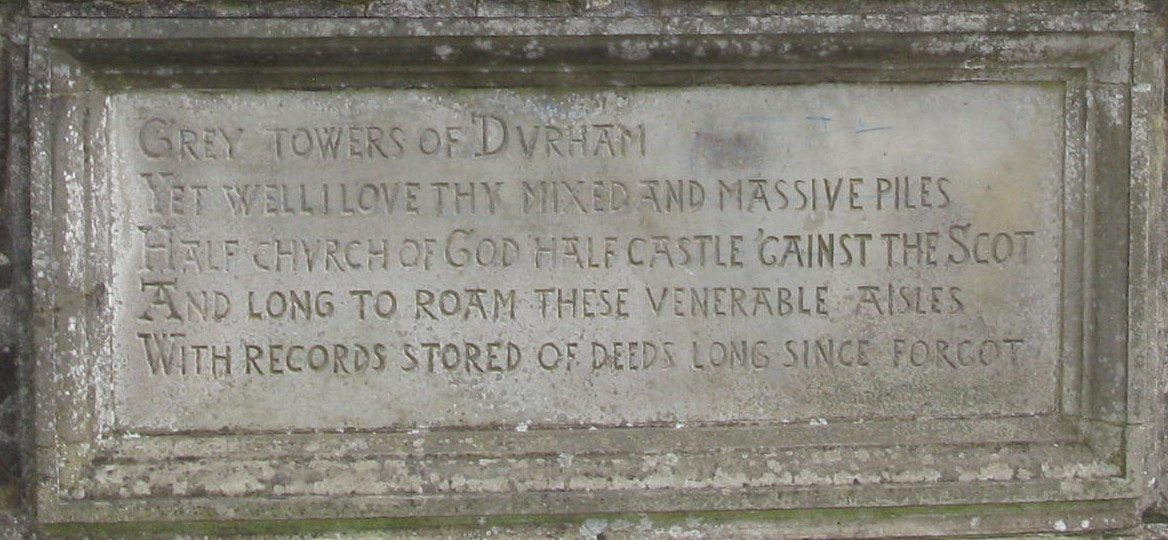

* * * * * Outside the heavy, chocolate-colored door to John Becx’s well-appointed office in London’s financial district, Richard Leader paced while clutching his documents. Richard had been in charge of the Braintree Ironworks operation in the Colonies, as agent for the Ironworks’ financial investors. By 1647, the Braintree operation was failing, and Richard found another location on behalf of the investors, north of Braintree on the Saugus River. He had been instrumental in getting the Saugus site built and operational, yet the investors lost faith in him. John Becx, a resident of London and a wealthy industrialist, was the lead investor for the twenty-four who financed the Ironworks. Richard had left the Colonies in the summer to meet with Becx in England. One of Becx’s aides opened the door, and Richard hurried into the office. Becx sat between heavy wooden supports for his over-sized desk. The legs of the diminutive Becx dangled from the leather-padded chair just above the floor. He ceased swinging them back and forth and said, “Richard, I provided the financing for the Ironworks, and my decision is final. John Gifford and William Awbrey are replacing you.” Richard raised a hand to stop Becx from saying more. “I come not to ask thee to reconsider,” he said. “Wise on your part,” said Becx as he slid off his chair to pace. “I respect your engineering talents. You built a magnificent ironworks, yet we still lost money.” He ceased pacing and turned to Richard. “What happened?” Richard squirmed. “Magnificent truly, but we lacked sufficient labor.” “How can that be?” asked Becx. “Governor John Winthrop was keen on our venture. Said it was important to his common weal. His son oversaw everything until you replaced him.” Becx’s eyes widened. “Aha, was it spite?” “Perhaps, it was spite.” Becx frowned, and Richard quickly continued. “No matter, the Governor is deceased, and John the younger is in Connecticut. The Winthrops will no longer interfere.” “Splendid, the situation is improved. Gifford and Awbrey will turn a profit.” “Doubtful, the problem is bigger than the Winthrops. It’s that damn colony.” Becx raised his head, seemingly wanting to learn more. “The men are clergy, or artisans, or farmers, and the rest are their goodwives and children. The Ironworks never had enough labor.” “Then we should have imported some laborers,” said Becx. “Impossible. The Governor determined who would leave England for his colony. He oversaw every ship that arrived and sent back the ones not to his liking.” Becx glared his skepticism and Richard added, “Well not every ship. Thou art a Dutchman, ye understand.” Becx smiled briefly and said, “But you still hired laborers.” “We trained a few yeomen. But we needed colliers, furnace men, and…” “You should have trained more yeomen,” interrupted Becx. “There are not enough men to train. Even so, it is a dear wage we pay. And force them to deliver a fair day’s work, why the constable, clergy, the whole town are upon thee.” Becx sighed. “I’ve read the court proceedings and paid the fines.” “They are all kin. It’s never a fair court.” “Less dear labor,” said Becx as he paced while pondering. “We need to reduce our costs.” He stopped and turned to Richard. “How about the natives?” Richard sneered. “With sincerest respects.” “Just a thought,” said Becx as he rubbed his chin. “Still a few ships with cheap labor could solve our problem.” “Governor Endicott would never allow it.” “Nonsense. A few ships will not spoil that new world experiment.” “But if he does object, what becomes of these undesirables?” asked Richard. “The Governor can determine their fate.” Becx pondered further and a smile crossed his face. He gave a concluding head nod and turned back to Richard. “Now, what’s your purpose today?” “A saw mill in the colonies,” said Richard as he laid out his documents. “Thou will make a fortune.” “And is Governor Endicott keen on this venture?” “The mill will be north of the Massachusetts colony, on the Piscataqua River.” “I like that,” said Becx as his smile broadened. “There is plenty of timber hither,” said Richard as he pointed to a spot on his map, “with a river to the sea. It’s ideal.” “And labor?” “It will be dear, but worth it.” Richard picked up his other documents. “I have computed the labor costs in these journals.” Becx grabbed the documents from Richard. “I admire your engineering skills, but you are not a financial man. I must study them further. Adieu Richard Leader.” As Richard turned to leave, Becx said, “You know Richard, if the Governor protests too much about undesirables in his Massachusetts, we could send them north.” “Be assured,” said Richard as he paused at the door, “he will protest.”  Durham Cathedral has stood for a near millennium as an example of advanced Norman Architecture for its time. The nave’s ribbed vault with pointed transverse arches supported on alternating slender composite piers and massive drum columns created an elaborate and complicated ground plan. The flying buttresses concealed within the triforium over the aisles allowed greater height, opening up wall space for larger windows. Situated on a promontory above the Wear River, the 217 foot central tower offers views of Durham and surrounding areas. Nearby, the Bishop of Durham resided in Durham Castle. The bishopric had military as well as religious leadership and power until the 19th century. Among the Cathedral’s collections are St Cuthbert’s relics, the head of St Oswald of Northumbria, and the Venerable Bede’s remains; the library contains one of the most complete sets of early printed books in England, the pre-Dissolution monastic accounts, and three copies of Magna Carta. The Cathedral has had a robust, glorious history except for the fall of 1650 when it achieved infamy. After the 3 September 1650 Battle of Dunbar, it became a makeshift prison for Scottish prisoners-of-war. Some 5,000 endured a ‘death march’ from Dunbar to Durham. Only 3,000 survived and arrived at the Cathedral to suffer more inhumanity, living largely without food, water, or heat. The prisoners destroyed much of the cathedral woodwork for firewood. Some 1,700 died while there and were buried in mass graves about the grounds. In “The Immigrant”, fourteen year old John Law survived his Durham ordeal to face another — a horrific, life transforming, trans-Atlantic crossing to the Colonies. Here is a day in his life:

Durham Cathedral, Durham, England Autumn 1650 As John lay on the Durham Cathedral floor, a speck beneath the towering Norman-styled arches, he pondered. Andrew Wright had been dead-on correct again. The English only took the healthy, and now John knew why. The sickliest of the more than 5,000 prisoners had perished on the eight day, 120 mile ‘death march’ from Dunbar, Scotland to Durham, England. Andrew Wright was still in Scotland, perhaps with his clan, and John was further from his mother. Maybe John had been less fortunate than he thought. Maybe the truly blessed ones were the 2,000 prisoners who littered a southern road into England. John lowered his melancholy eyelids, and when they reopened, he contemplated the designs on the arches. His usual worship place was Spartan by comparison. Even the church, which his father insisted John attend the year before he died, couldn’t compare to this magnificent mammoth structure. The walk to that Scottish church was cold and lengthy, and John complained constantly. But his father was resolute; John needed to witness what his father had witnessed as lad. As John reminisced, he appreciated his father’s insistence. That church was candlelit, insufficient to heat its stone structure, but sufficient to warm John’s heart. The cleric’s robe swooshed as he moved about the altar. An organ shattered the stillness, and the congregation sang. The shivers, which John had then, returned. He inched close to his mother since her sweet warble was more appealing than his father’s off-key monotone. Her mouth and lips changed with each syllable, and when she smiled at him while singing, his body prickled. The walk home was neither cold nor lengthy, but silent, except for crunching feet on the meadow’s rime and his mother’s hum of a previously sung hymn. Durham Cathedral’s stench grew overwhelming, and John ceased daydreaming. Vomit and urine splotches, excrement in nooks, doses of rotting bodies and traces of disease from those waiting to die created a noxious concoction. Even Durham Cathedral’s towering arches were insufficient to allow the stench to dissipate. John wiggled his nose and rolled to his side. One stained glass window still remained intact. Jesus, with inviting open palms hanging at his side, stared back. John had prayed to that window, but God hadn’t hear him. He glared at Jesus and thought about praying again, but he rolled away and became captive to the nave’s ribbed arches that formed part of the Cathedral’s vault. As twilight came, the predictable feeding clamor ensued and distracted John. He arose and noticed a desperate, thin, and seemingly familiar wretch, pleading with a guard. Coins fell into a guard’s open palm, bread was handed over, and the wretch backed away. John’s memory was finally triggered. It be MacTavish. But he nae be a fat bastard. He wondered if God had rendered justice after all. MacTavish, the swine, ate his fill at Dunbar, and the English probably mistook him as hearty. Now, he grovels for swill and is forced to live in this hell with the rest of us. John smiled as his eyes rose up the arches and through the ceiling. He nodded a ‘thank you’ to God. But God didn’t acknowledge it. Only Andrew’s earlier words echoed down from the arches. “MacTavish’s coins will pay for safe passage after Cromwell prevails.” John whirled to the stained glass window of Jesus, but he couldn’t maintain eye contact with him. He thought further as MacTavish moved out of the nave toward the choir section, before disappearing into the darkened recesses of the aisle on the south side. As John waited for his food, Malcolm’s previous boast throbbed in his temples. “Me will slay MacTavish and take his coins.” The words continued to resonate while John ate. When John finished eating, he moved toward the choir section. When he caught a glimpse of Jesus, he moved back to the nave. He sprawled onto the stone floor, allowing the Cathedral’s drone to be his lullaby as he tried to sleep. Unlike his mother’s soothing tones, this lullaby was a jumble of scuffles, raised voices, thumps and howls, which dimmed to murmurs. But this night, a persistent thought accompanied the lullaby. Slay MacTavish and take his coins for safe passage home. John couldn’t sleep, and he arose and drifted toward the darkness again, unsure of what he would do. A broken, jagged-edge spindle from the altar rail lay on the floor of the choir section. It seemed to beckon, and John grabbed it and held it like a dagger. He moved to the darkened recesses near the small arches that formed the aisle of the choir section’s south side. Using the aisle’s outer wall for bearings, he stepped further away from the nave while searching for MacTavish. When he saw a silhouette of a man just ahead, his heart raced as his vision blurred. MacTavish? Propped against that column? MacTavish’s ashen cheeks were noticeable in the darkness and seemingly summoning John. He raised the altar spindle and took deliberate steps. As he drew closer, John noticed MacTavish’s eyes were opened, and he held his last step in mid-air. His thigh began to quiver. Me God, does he see me? John lowered his leg slowly. MacTavish hadn’t noticed. He inhaled while contemplating his next step, still unsure . . .  On a blustery April 7, 1844, Joseph Smith stepped to the podium to address the congregation gathered for the general conference. Smith’s friend, Elder King Follett, had died a month earlier from accidental injuries. As Joseph scanned the more than twenty thousand gathered on the banks of the Mississippi, they expected he would eulogize his friend’s tragic death. Smith splayed his arms and said, “May the Lord strengthen my lungs and stay the winds.”  Smith went on to deliver his most important sermon. In Richard Lyman Bushman’s book Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling, he notes that literary critic Harold Bloom called the sermon ‘one of the truly remarkable sermons ever preached in America’. As Smith concluded, the clouds had parted, sun shone on Nauvoo, and the winds had been stayed. Within three months of his eloquence, an angry mob murdered Smith and his brother while they were in a Carthage jail cell. In The Believers in the Crucible Nauvoo, amid controversy swirling in Nauvoo on 26 May 1844, George Taggart reflected on his prophet’s words delivered earlier. Below is the relevant part of the chapter.

__________________________________________ As George waited to hear from Joseph Smith, he reflected. Several weeks earlier, he had attended a general conference, which occurred shortly after the death of Elder King Follett. Joseph took the occasion to speak about death in general rather than eulogize his friend’s tragic demise. George had hoped for inspiration since at the time he was still grieving his father’s and Oliver’s deaths. He received more, which now replayed as he waited. On that day, Joseph approached the podium as dark clouds loomed and trees swayed. He gripped his lapels and said. “May the Lord strengthen my lungs and stay the winds.” The leaves continued to flap, yet George heard every word Joseph had said. “God himself was once as we are now, an exalted man, who sits enthroned in yonder heavens. If the veil were rent today, and God was made visible, you would see him like a man — like yourselves.” When George first heard those words, he was confused. “How can I or any man become a God?” But as quickly as he had questioned, the Prophet answered. “When you climb a ladder, you must begin at the bottom and ascend step by step until you arrive at the top; and so it is with the principles of the gospel—you must begin with the first, and go on until you learn all the principles of exaltation.” As the Prophet continued to expound, George reflected on his life. He had taken his first step toward exaltation when he was baptized, and his father’s and brother’s deaths had brought him higher up the ladder, closer to God. “Am I becoming more Godlike?” He had pondered, still unconvinced and hoping for answers. “The mortal body has a beginning and an end. Thus, here is your eternal life; to know the only wise and true God. Learn to be Gods yourselves by going from a small degree to another, from grace to grace, from exaltation to exaltation, until you sit in glory with those who sit enthroned in everlasting power.” As Joseph continued, George had realized mortal existence is brief and the spirit is eternity, a spirit the same as God. As the sermon ended, the clouds had parted, creating darkness on either side of the blue skies above Nauvoo; and the winds had been stayed. As George left, he had an enriched view on living his life - as he was now, God once was; and as God is now, he could be. Soon after Joseph’s King Follett sermon, the apostates had proclaimed Joseph a fraud saying, “Mortal men becoming Gods is utter blasphemy.” The apostates’ rhetoric continued, and William Law, the most outspoken, accused Joseph of adultery, creating deeper church schisms and fanning anti-Mormon flames. The hullabaloo that followed continued to trouble George. Now as Joseph arose to speak, George prayed he would respond and vanquish the apostates’ mistruths. Joseph’s stride lacked its usual vigor. His smile seemed contrived. He appeared as beset upon as George was feeling. He didn’t grip the podium with authority, but slouched, using it as a crutch. His opening remarks were barely audible. George feared his Prophet’s recent tribulations had taken their toll. But Joseph cleared his throat, and a vigor came into his voice. . . .  At sunrise on 10 February 1676 during King Philips's War. Native Americans attacked the remote town of Lancaster, killing thirteen and taking over twenty-four captive, among them Mary Rowlandson and her three children. Her six year-old daughter succumbed from her wounds after a week of captivity. For eleven weeks, Mary and her children were forced to accompany their captors as they raided other settlements and eluded the English militia. On 2 May, Concord’s John Hoare paid a £20 ransom while at Redemption Rock in Princeton, and Mary’s ordeal ended.  I likened her ordeal to the 1980 Iran hostage crisis. Americans suffered along with those hostages, and I imagined the Puritans, particularly the good wives, empathized with Mary's plight. I was in church the day following the hostage release. Instead of a processional hymn, the organist played the National Anthem. I still feel the goose bumps that overcame me at that time. John Hoare negotiated Mary’s release, and during my research, I grew to admire this courageous, independent-thinking Concord lawyer. He appears several times in “The Immigrant”. Below is the scene where he rescues Mary. Maybe God’s providence is that I shall be bounded into captivity like Joseph to the great Pharaoh, thought John Hoare. His two Indian escorts reflected similar doubts. Hoare’s eyes moved from his escorts, past several young natives to the gathering Sagamores. The young natives seemed to reflect more loathing than the wise council of Sagamores, who were deciding the fate of two lone English, Mary Rowlandson and himself.

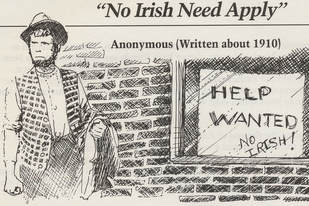

He studied the Sagamores further and thought. I know the Indian mind so well, and how to deal with them. He ceased his study and rubbed his forehead. Beware the barrister so full of his bounty, for he will yield nothing. Hoare moved back to his limp satchel. But I will not fail. When Hoare arrived two days earlier, the satchel had teemed with ransom for Mary’s release. Such a welcoming; gunshots whistled under his horse, accompanied by ear curdling whoops and eye shocking gestures. Hoare thought then the offer of negotiations was but a ruse. But if it had been, he would be dead and the entire ransom would be gone. No, the welcoming was just the opening salvo. But Mary, upon hearing the commotion, must have believed her hope of release had been snuffed out before the negotiations started. Most of the ransom, tobacco, trading cloth and twenty shillings, had been stolen in the night. Hoare wondered again if it was a ruse, or just an Indian custom of immediately enjoying the rewards of negotiation. The Sagamores were still discussing among themselves, a few utterances were decipherable, but reading expressions was useless. The only certainty was there wasn’t unanimity. Mary’s captor would hold the most sway, and he had to be convinced to release her. Her captor had dressed for the feast the night before in a Holland shirt with silvery buttons and white stockings. Shillings jangled from his garters and wampum rattled from his chest as he danced in the night. His squaw danced, too, in a kersey coat, red stocking, and wampum girdles from the loin up, with jingling bracelets and swaying necklaces. The Indians drummed on kettles throughout the night to sustain the frivolity. Now as twilight moved in, Hoare slipped his hand into his satchel. He pushed aside a protecting cloth and fumbled for the feel of glass. It was his last hope. He looked back to the Sagamores, who were in animated discussion. He glanced skyward and thought. Am I Daniel in the lion’s den? Is it thy providence for an angel to shut these savages’ hungry mouths or will they devour me once they’ve tasted Satan’s evil? He slipped a glass flask into his waistcoat and was led to the wigwam of Mary Rowlandson’s captor. As he entered, her captor arose and stood, unsmiling and seemingly still fatigued from the night before. Hoare offered him the spirits as negotiated earlier. He gulped and then shuddered. “Thou art a good man, John Hoare,” he said. His good English dialect, which he had previously learned from missionaries before leaving them, was still prevalent. He sat on the ground and motioned for Hoare to do likewise. Hoare’s rheumatism had returned during the ride from Concord, so sitting, ankles crossed, would be difficult. But not to comply might foil the negotiations. He struggled to the ground, pulled his ankles together, and splayed his legs. The intermittent gulping continued, and Hoare’s doubts increased with each swig. The quiet was unnerving and finally Hoare broke it. “Where is Reverend Joseph Rowlandson’s Goodwife?” Mary’s captor raised the flask, and Hoare hoped it meant in due time. Hoare’s Indian escorts had assured him Mary would be released if he offered alcohol to him. He trusted them, but the gulps were now savoring sips. Were the spirits taking hold? thought Hoare. “I demand to see Mary Rowlandson, before thee take another swig,” he said. “Thou art a rogue, John Hoare,” and the Indian eased the flask to his lips. He licked the rim and sipped. His head lunged forward, and Hoare recoiled. Several more menacing gestures came, followed by a laugh and another sip. As the Indian muttered, Hoare waited with the patience of Job. “Thou should be hanged John Hoare. Thou art a rogue.” Hoare wrung his hands and shifted his bottom to ease his knotting leg muscles. The flask was emptying, and once gone, indeed, maybe he would be hanged. The Indian’s muttering turned to shouts in his native tongue. As his rant continued, Mary and his squaw entered the wigwam. The pint was pointed in Mary’s direction, and the Indian’s words slurred forth. “Thou hast served me and my squaw well. Thou art a good woman.” Mary stood trembling and turned to Hoare. She wanted a nod or any sign of assurance from him. But Hoare had none to give as he was as uncertain as her. Mary’s captor continued to talk, now with civility, and her trembling eased. After another sip, his squaw spun away and left the wigwam. Mary’s captor struggled while arising. He steadied his teetering and weaved out of the wigwam. Mary and John remained quiet, listening to the commotion from outside, occasionally looking to one another and allowing their facial expressions to be their communication. The commotion ended, and Mary said, “Ye spirits have certainly had an effect.” “Ye spirits were given in good faith,” said Hoare. “I know, but there are so many to please; King Philip, the Sagamores, my master, my mistress. I sold the tobacco you brought to please Philip.” “My satchel is nearly bare. Thy ransom hath all but been consumed. I know not what comes with the morn.” “As with every morn, John Hoare, Esquire, God’s divine providence will come.” “Thy words are apt. They could only have been spoken by the Goodwife of an honored Reverend.” Hoare and Mary spent the rest of the night wondering if their ordeal would end. The next morning, Hoare’s Indian escorts came with two horses. John Hoare’s most difficult negotiation of his life had been successful. Two English people rode through the wilderness and reached Lancaster by sundown. Mary’s infant child had died while in captivity, and her two older children had been separated from her. Lancaster, which lay deep in the wilderness, and where her husband came to be its first Reverend, was now an unoccupied rumble of ashes – more of God’s divine providence. Mary’s one consolation was her husband had been in Boston when the attack occurred eleven weeks earlier. As news of Mary Rowlandson’s rescue swept across the Colonies, a sense of triumph came to Concord. For Lydia Law, who had lived Mary’s ordeal, it was liberation from her self-imposed anguish. John Law now was re-energized and undertook his annual spring chores readily. His sons sensed their parents’ optimism and renewed enthusiasm, and their outlook changed too. Stephen’s nightmares ended, and John Junior no longer had to pretend to be a brave older brother.  For background before writing “The Believers In The Crucible Nauvoo”, I read Carol Cornwell Madsen’s book “In their Own Words – Women and the Story of Nauvoo” These pioneers through their letters, diaries, and writings poignantly capture the mosaic that was Nauvoo, women speaking in their own voices. Three days before Vilate Kimball wrote to her husband Heber, Joseph and Hyrum Smith had died, and John Taylor and Willard Richards had been severely wounded. Heber and the remaining seven of the Quorum of Twelve were away on mission. Thus, Nauvoo was leaderless while under siege. The entire letter Vilate wrote can be found in Dr. Madsen’s book. Below is a scene using excerpts from her letter.  Through a rain-spattered window, Vilate Kimball watched Brother Adams head home. A few Saints hurried while trying to avoid puddles and streams that cut paths to lower lying areas. As she allowed the curtain to drift from her hand, she realized the dreary images were alike her thoughts and Nauvoo’s mood. She picked up a quill to do a frequent task, write to her husband away on mission. In 1822, a sixteen year old Vilate married Heber Kimball. They, along with Brigham Young’s family, were among Joseph’s early followers. In 1832, they moved to Kirkland, then to Missouri, and to a hopeful last stop in Nauvoo. Elder Kimball became an apostle in 1835 and was often away. Vilate had endured much -- disruptive moves as the Saints fled, prolonged absences of her husband, loss of some children, and the introduction of plural marriage -- yet she remained steadfast to her husband and her Church. She began to write: Nauvoo 30 June 1844. My dear dear companion, Never before did I take up my pen to address you under so trying circumstances as we are now placed. But Brother Adams, the bearer of this, can tell you more than I can write. I shall not attempt to describe the scene that we have passed through. God forbid that I should ever witness another like unto it. I saw the lifeless corpses of our beloved brethren when they were brought to their almost distracted families. Yea, I witnessed their tears and groans, which was enough to rend the heart of an adamant. Every brother and sister that witnessed the scene felt deeply to sympathize with them. Yea, every heart is filled with sorrow, and the very streets of Nauvoo seem to mourn. Where it will end the Lord only knows. She paused as grief overcame her. The quill shook, but knowing Brother Adams would soon return, she gripped her writing hand to ease its trembling. The quill scratched the paper breaking the silence as she wrote amid dank air: We are kept awake night after night by the alarms of mobs. These apostates say, ‘their damnation is sealed, their die is cast, their doom is fixed’, and they are determined to do all in their power to have revenge. William Law says, ‘he wants nine more that was in his Quorum of Twelve ’. Sometimes I am afraid he will get them. I have no doubt but you are one. The thought of William Law slaying her husband loomed as she continued writing. Overcome, she paused to wipe a tear away. More tears came, and she drew back so they wouldn’t splatter the paper. She wiped her eyes with her sleeve and continued. Her mind swirled in confusion, and she was unsure what she was wrote until she neared the end: My time is up to send this, so you must excuse me for I have written in a great hurry and with a bad pen. The children all remember you in love. Now fare you well my love, till we meet, which may the Lord grant for his son’s sake. Amen. Vilate Kimball  Do today’s immigrants face challenges akin to previous waves of foreigners; or is it different ? The Great Migration (1630 - 1640) consisted of twenty thousand, primary English immigrants trekking to a new world in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. This wave was ground zero, a beginning for what would eventually become America. They dealt with the indigenous people in various way to claim the land and built for themselves a Puritan Theocracy, free of diversity. For a decade the Puritans had their way until another wave, perhaps more appropriately, a trickle of Scottish Prisoners of War arrived in 1651 — Immigration 1.0. These invaders of an erstwhile virgin land spoke differently with a Scottish burr, were Presbyterians not Puritans, and worst of all had fought against the Puritans’ guardian, their beloved Oliver Cromwell. To some, they were the enemy, and to others, a cheap source of labor for the Saugus Iron Works. The Great Migration had consisted of family units often bound by kindred ties or by residing previously in the same English village. These Scots were young males, rowdy, and lacking the discipline that marriage and a family require.  Immigration 2.0 and succeeding versions followed. The Great Potato famine (1845 - 1849) caused mass starvation, disease, and desperation, and a wave of Irish came to America. By 1850 these Catholics made up a quarter of Boston’s once Protestant population. By the 1860s, NINA (No Irish Need Apply) accompanied help wanted signs. A song of the same name became popular in 1862 in London, which Irish-Americans adapted the lyrics to reflect the discrimination they felt as they sang. Later, French Canadians streamed down from Quebec, cheap labor to work the textile mills along the Merrimack River in Manchester, NH, and Lowell and Lawrence, Mass. By the mid-twentieth century, French-Canadian Americans comprised thirty percent of Maine, and towns like Lewiston had their enclaves known as “Little Canada”. Similarly, at the turn of the last century Italians arrived, congregating in an enclave in Boston’s North End. Like the waves before, they faced challenges - poverty, discrimination, and a language barrier. They were full of emotion and more swarthy than the reserved, pale Yankee Puritans who were Boston’s establishment, seemingly under siege. And the waves continue. Today, Hispanics and Muslims are in the news. Even on this tiny island of Martha’s Vineyard, we have a significant minority of Brazilians. Some come seeking jobs and, as a source of cheap labor, their opportunities abound. They seek a new start, some seek asylum. They speak different languages, and certain groups are viewed by some Americans as terrorist, the enemy similar to the view some Puritans had of the Scottish Prisoners of War who arrived 367 years earlier. The more things change, the more they stay the same. Did John Law face greater discrimination than subsequent immigration waves would face? And how about today’s immigrants? If you read The Immigrant, you might find some answers to these questions.  When I tell people The Believers In The Crucible Nauvoo is about Naamah Carter who becomes Brigham Young’s plural wife, some, particularly males, elbow my ribs while offering a lecherous, “Heh, heh.” Others mention the sensational headlines about Warren Jeffs, the FLDS President, or the HBO series “Big Love”. A few do not realize the LDS church received a revelation and banned polygamy over century ago, paving the way for Utah to become our 45th state. Joseph Smith received his troubling revelations to engage in plural marriage three times between 1834 and 1842 before finally acting upon it. In May 1843 with his wife, Emma, at his side, he entered in “celestial marriages” with Emily and Eliza Partridge, servants in his household. Soon after, Emma rued her decision. As the Female Relief Society of Nauvoo’s President, she spoke out against plural marriage and, eventually in March 1844, Joseph suspended their meetings. Joseph is believed to have had twenty-seven “celestial wives”, which was determined years after his death and, each is supported with varying degrees of objective evidence.  Brigham Young on the other hand is far more complex. Facts vary on what constituted a marriage and when it may have occurred. Throughout Brigham's life, he was less than forthcoming about his marriages. Some historians have him with fifty-five wives and fifty-nine children from sixteen of those wives. One wife, Emmeline Free, bore him ten children. Thus, many were childless, begging a question if some of those marriages were conjugal. In January 1846, the month preceding the exodus west, Brigham wrote in his diary he work in one stretch twenty hours a day for a fortnight, endowing the faithful and overseeing the Herculean task to cross the Mississippi and endure a harsh prairie winter as wandering nomads; and he married nineteen women, including his widowed mothers-in-law from his first and second marriage and a widowed sister-in-law. Neither these women nor several others he married in the January bore him children. Surely, Brigham’s reasons for marriage varied. Naamah Carter married Brigham in January 1846. She was twenty years his junior, recently widowed, virtually alone, and dedicated to temple work. What were Brigham’s reason for proposing marriage to her, and how much soul searching did she undergo before saying, “yes”? The Believers In The Crucible Nauvoo offers answers to these questions as it unfolds this unusual love story. If you desire a robust insight to plural marriage, you might read Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s recent work A House Full of Females. |

AuthorIn 2002, Alfred Woollacott, III retired from KPMG and began pursuing his family history. His research is meticulous and in December 2017, he began blogging about it, giving further insight to his novels Archives

August 2019

|

- Home

- About the Author

- Blog

-

"The Immigrant"

- Author's Interview

- Published Reviews of The Immigrant

- Resources for The Immigrant

- 3 September 1650 Dunbar Scotland

- November 1650 On the North Atlantic

- Early Winter 1650 - 1651 Charlestown, Massachusetts Bay Colony

- 22 April 1676 Concord, Massachusetts

- August 12, 1676 Miery Swamp Bristol, Rhode Island

- "The Believers"

- Other Timelines

-

Alfred's Four Legged Stool

- Eleven Generations of John Law Descendants

- John Law of Acton, Massachusetts

- Reuben Law of Acton, Massachusetts and Sharon, New Hampshire

- Re-dedication of Woollacott Square, 26 May 2015

- John Woollacott of Atherington, Devon, England, patriarch of the Fitchburg Woollacotts

- The Woollacotts of North Devon

- Early Woollacotts and Variations thereon

- Élisabeth Isabelle Salé, Les Fille du Roi

- Jill's four legged stool

RSS Feed

RSS Feed